Architecture as a tool

You learned in the previous paragraphs that organizations become more and more dependent on information and information technology, and that organizations have different strategies to compete in their markets. This puts demands on IT planning. This is how Service Oriented Architecture emerged, to cater for these needs. Before we dive into Service Oriented Architecture, it is important to define architecture.

Architecture is a discipline that helps organizations to align the IT with the business and the strategy of the organization. In the construction world, architecture is a well-defined discipline. The profession is protected; not everybody can call him or herself an architect. But in IT, we lack clear definitions of roles and capabilities. In different countries, industries, and communities we use different definitions. Although we will define architecture in this paragraph, and adhere to de-facto definitions and standards, there is no consensus in the world of IT. So if in your company, you employ different names and titles for the activities described as follows, that is fine. It is important that activities are executed, not what you call them or who executes them.

Time for a definition, ISO/IEC 42010:2007 (http://www.iso-architecture.org/42010/cm/ ) defines architecture as:

The fundamental organization of a system, embodied in its components, their relationships to each other and the environment, and the principles governing its design and evolution.

The Standard takes no position on the question, What is a system? In the Standard, the term system is used as a placeholder. For example, it could refer to an enterprise, a system of systems, a product line, a service, a subsystem, or software. Systems can be man-made or natural.

What is important in this definition is the scope of a system. In the following paragraphs, we describe different types of architecture, defined by the scope of the project or the system. For example, if we are describing the architecture of a municipality, the system is everything within the municipality. If we are describing or designing the IT landscape for the front office, the scope of the system is the front office IT. But if a project is about implementing a new regulation, then the scope of the system we are describing is everything that is impacted by the new regulation.

It is important to note that architecture does NOT equal standardization. It depends on your company's strategy or operational model, how much integration and standardization you need and in what processes and systems and organizational parts you need it. The goal of architecture is to translate the business strategy into appropriate guidelines for standardization and integration. Architecture is a means to an end; making sure that IT can fulfill the business requirements is the goal, not standardization, or documentation.

To make sure that the architecture meets the demands of the business, Zachman (http://www.zachman.com/about-the-zachman-framework) defined a number of questions that need to be answered when creating the architecture of the system. They are: Why, how, what, who, where, when, and what-if? Consider a company that sells printers, faxes, and other peripherals and wants to redesign their outdated front office architecture. To make sure the front office architecture is aligned with the goals of the company, the following questions need to be answered:

Why: What are the goals of the organization with regards to the front office? Do we want to encourage customers to use the phone or the website? Do we cross-sell or up-sell on the phone? Do we want to minimize the time spent per customer or maximize customer satisfaction?

How: What type of functionality should the IT systems support in the front office? Do the users need to look up payment history? Do we need to see previous purchases from this customer? Do we need to change data directly or just put in requests to be handled in the back office?

What: What types of data do we use and store in the front office? Do we have all customer related data in the front office? Do we store the same data the customer can see, or more, including everything that is known in the back office?

Who: Who is using the systems in the front office? What is the education level and experience of the target users? How many users are working in the front office, are they working with the systems all day?

Where: Where are the systems of the front office, what does the network look like? Are the systems located on-site, or does a remote provider host them? Are the users on-site, or using the systems remotely from home?

When: What type of availability do we expect of the front office systems, 24/7 or office hours? The systems that support the call centers and website probably need more availability than the systems that are used by the employees at the office.

What-if: Is there an alternative way to deliver the solution? What if we outsource the front-office activities?

The answers to these questions depend very much on the perspective or stakeholder. If we are talking about the IT landscape of the front office from a security perspective, we have different interpretations and focus for the why, what, how, who, where, and when questions compared to the perspective of the controller, who is paying for the new system. For example, from a security perspective it is important to differentiate roles that have different permissions and responsibilities. The who question will focus around that. From a financial perspective, it is more important how many users there are, not what they do exactly. The answer to the who question from a financial perspective will be focused more on actual number of users, and less on the roles and types of users.

Because of these different perspectives, there are several ways of breaking up the organization of a system or architecture. Systems can be divided into logical layers, tiers, or viewpoints/views:

When we divide everything in a municipality in business, information, and technical topics, we are talking about layering of the architecture

When we divide software in the front office in presentation, business logic, and data parts, we are talking about logical tiers in the software

When we describe the system differently depending on the perspective of the stakeholder, we say we are describing a view of the architecture from a specified viewpoint

While viewpoints, layers, and views refer to logical concepts, tiers often refer to physical division.

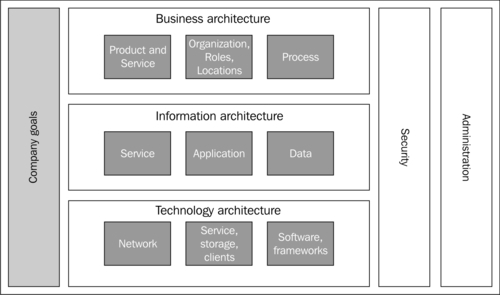

Layering of architecture

There are different layering schemes used by different architecture frameworks. A common layering in architecture is dividing it in three main layers: the business layer, information systems layer, and technology layer. This is the layering applied by The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF). In this framework, the information systems layer is divided in services or applications and data. Other layers can be divided into several layers too. Whether a layer is a first-class citizen or part of another layer can be cause for great debate within organizations. To keep things manageable we use the three layers (Business, Information, and Technology) of architecture throughout the book, with different parts within the layers as shown in the next figure. Security and Administration cut across the three layers, so they are positioned next to these layers.

Layers and aspects within these layers can be described from different perspectives: strategic, tactical, or operational. The security view is written from the viewpoint of the security officer. The administration view is described from the viewpoint of the system administrator. The other layers are not written from a specific perspective, but are divided according to the type of information that is captured from the system. For example in the business architecture, one typically finds information about the business processes. This can be described from different perspectives, for example from the perspective of the operation, or from the perspective of a controller. The same is true for information in the other layers.

Models

Architecture is often expressed using diagrams and models, apart from text. There are different (formal) modeling languages available to model. All models target different stakeholders and have a different scope. The following table shows modeling languages that can be used in the different layers together with their target architecture. Apart from these formal modeling techniques, diagrams can be created that are free format. Depending on your target audience and your own modeling skills you can pick any of these languages to communicate the architecture of your system.

|

Modeling language |

Scope |

Standard/ Proprietary |

Target audience |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Archimate |

Business, information, and technology layer |

Standard (The open group) |

Architects, developers |

|

UML(Unified Modeling Language) |

Business, information and technology layer |

Standard (Object management group) |

Developers, architects |

|

BPMN (Business Process Modeling Notation) |

Process models |

Standard (Object management group) |

Process analysts, business consultants |

|

EPC (Event driven Process Chain) |

Process models |

Proprietary |

Process analysts, business consultants |

|

ERM (Entity Relationship Model) |

Information (Data) layer |

De-facto standard (There is no official standardization body that maintains ERM) |

Developers, architects |

|

Not applicable (Free format) |

Business, information, and technology layer |

Proprietary |

Entire organization |

Note that in this book, we will use mainly UML diagrams, BPMN diagrams, and free format to describe the various concepts and architecture examples.

Requirements

Architecture is not a means to an end, but a way to assure that organizations can change and meet market demands, and that they operate efficiently. To accomplish this, the following architectural requirements are imposed on the architecture by the organization:

It is understandable to the stakeholders involved.

It is well known and visible in the organization.

It is useable. When a project is started or the organization has to take decisions, the architecture will help make this decision or scope the number of possible solutions for a problem. This means that it should have clear principles and guidelines, and use terms and layering that are valuable for the organization.

It can be changed. Because organizations change, the architecture needs to change as well. It is not a cookie cutter that keeps its shape; it is a plan that will have multiple versions as time passes.

This list applies to any architectural style or reference architecture you choose for your organization. When you notice that architecture is described in your organization, but not used in projects or within the decision making process, one of these requirements is not met. Instead of continuing to describe the architecture, it is important to investigate which of these requirements is not met. Common pitfalls are that the architecture is too detailed, out-dated or too complex.

Architecture ontology

In this paragraph you will learn about the different types of architecture that you can apply or use for your organization to ensure business and IT alignment. This will put Service Oriented Architecture in perspective and helps you chose the right scope for your efforts. There are two different axes on which you plot architecture; one is scope of the system, the other one is generalization. Scope can be really big, or specific and small. As you recall from the definition of architecture, the scope of the system it describes can be anything. In this paragraph we discuss enterprise architecture, project architecture, and software architecture, as examples for scope of the system. Apart from scope, there are also grades of generalization that you can put in architecture. You will also learn about reference architecture and solution architecture. Last but not least you will learn about a specific type of solution architecture—Service Oriented Architecture—as an introduction to the rest of this book.

The figure shows the relationship between the different architecture types. As you can see, Service Oriented Architecture is a reference architecture that guides and constraints solution architectures. The reference architecture can have different scopes such as Enterprise architecture, Project architecture, Software architecture, and so on.

Enterprise architecture

If the scope of the architecture consists of the entire company or organization (enterprise), or the architecture scope spans multiple organizations, we practice enterprise architecture. Enterprise architecture as defined in Enterprise Architecture As Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution, Ross, Weill, and Robertson, Harvard Business Review Press:

Enterprise Architecture is the organizing logic for business processes and IT infrastructure, reflecting the integration and standardization requirements of the company's operating model. The enterprise architecture provides a long term view of a company's processes, systems, and technologies so that individual projects can build capabilities, not just fulfill immediate needs.

There are several frameworks and methodologies available for enterprise architecture. One of the first frameworks that became a basis for other frameworks is the Zachman framework. It is a framework for structuring the enterprise architecture and consists of a matrix of 6 x 6. The columns consist of questions we mentioned earlier. The rows are organized from high level to more detailed as can be seen in the following screenshot from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zachman_Framework):

An architect describing the enterprise architecture using this framework needs to decide what columns and rows need to be described for the organization/enterprise. Not every cell needs to be filled. For example, if the focus is on introducing Business Process Management into an organization in order to get rid of functional silos, the How column needs to be filled with process models, diagrams, and execution details. If the different locations of a company are critical the Where column needs to be described. The same applies to the rows, depending on the needs of the organization more or less rows can be described.

Open Group offers another comprehensive framework—TOGAF. It consists of several parts:

Architecture Development Method (ADM): It describes the methodology.

Content framework: It contains deliverables, artifacts, and building blocks.

Enterprise continuum and tools: This is a view of all the different types of solutions and architectures, ranging from detailed to abstract, for different types of stakeholders.

Reference models: TOGAF offers generic reference models that can be used as a starting point for organizations to structure their own enterprise architecture.

Architecture Capability Framework: This framework explains the capabilities an organization needs, or the roles and responsibilities, to maintain the architecture.

There are several other frameworks that can be used. When you choose a framework, pick one that fits your purpose best. Some frameworks are more elaborate than others; some frameworks focus on both the organization of the system and on the process of designing it. Others focus only on the process, or the system. After choosing a framework, you will have to adapt it to the needs of your organization.

Reference architecture

There are a lot of similarities between different organizations in the same industry. For this reason, reference architectures are developed. Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reference_architecture) defines it as:

A reference architecture in the field of software architecture or enterprise architecture provides a template solution for an architecture for a particular domain. It also provides a common vocabulary with which to discuss implementations, often with the aim to stress commonality.

Using reference architecture has several advantages:

Standardization of terminology, taxonomy, and services eases working with suppliers and partners

It reduces the cost of developing enterprise architecture; the organization can focus on what sets it apart from the reference architecture and other organizations in the industry instead of reinventing the wheel

It makes it easier to implement commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software, because common terminology and processes are used

Obviously, it also has some disadvantages:

It takes some time to learn industry reference architecture; they are often (over) complete

The reference architecture is typically written by a group of people from different organizations and so is the result of a compromise

As we saw in the previous image, and in the definition of reference architecture, the scope of the reference architecture can differ.

Examples of (enterprise) reference architectures are the Dutch Government reference architecture—NORA (http://e-overheid.nl/images/stories/architectuur/nora_maart%202010-eng.pdf), TM Forum Frameworx and eTOM for telecommunications (http://www.tmforum.org/), and the US reference architecture for federal government, Federal Enterprise architecture—FEA( http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/e-gov/fea).

Solution architecture

Solution architecture is a detailed (technology) specification of building blocks to realize a business need.

Open Group recognizes different types of solutions in the solution continuum:

Foundation solutions: This can be a programming language, a process or other highly generic concepts, tools, products, and services; an example of a process is Business Information Services Library (BISL).

Common systems solutions: For example CRM systems, ERP systems as we have seen in the previous examples, and also security solutions.

Industry solutions: These are solutions for a specific industry. They are built from foundation solutions and common systems solutions, and are augmented with industry-specific components.

Organization-specific solutions: An example of this is the solution for the health insurance companies that want to offer self-service to prospective clients. The solution architecture describes the multi-channel solution for the organization, the tools and products that are used to implement it, and the relationship between the different layers.

The difference between reference architecture and solution architecture is that reference architecture is a generic reference where common problems are described together with principles and constraints on how to solve these. Solution architectures describe a specific solution to solve a specific problem or problems. For example, the Dutch reference architecture NORA is used as a reference for the solution architecture in a municipality.

Project architecture

Project architecture defines what part of a solution architecture will be realized by the project, or is in scope. This can overlap with a solution architecture if there is only one project needed to realize the solution architecture. If the solution is too big for one project, or there are different parts that are assigned to different projects, the project architecture describes what part of the solution architecture will be realized in the project.

Project architecture serves two purposes:

Guarding the enterprise or solution architecture: A project is typically focused on short-term goals. The project architecture explicitly describes what part of the project is supposed to satisfy long-term strategic goals, what deviations from the target architecture are going to occur and how these will be resolved in the future.

Provide input for, or change the enterprise or solution architecture: Enterprise architecture and solution architectures need to be adjusted based on experiences from projects and the current situation. Valuable feedback about the usability and understandability of the architecture is gathered from projects.

Reference architecture can also have the scope of a project. The project architecture is then less specific than solution architecture and contains guidelines, principles, and constraints for projects in the organization in general.

Software architecture

Software architecture is focused on the structure of the software. It can be viewed as a special type of solution architecture, project architecture, or part of the technology architecture. The target audience of these types of architectures are developers. Often these are not referred to as architecture, but rather as software design.

Service Oriented Architecture

We saw earlier on in the chapter that for companies that apply product leadership or customer intimacy as a strategy, flexibility is key. One of the possible solutions to make sure that IT is flexible and can be easily changed is by applying a solution architecture based on Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). Service Oriented Architecture is a reference architecture that can be applied in organizations that are part of a (supply-) chain or network, and organizations that have to deal with a lot of regulatory changes, or fast-changing markets. It makes it possible to change parts of the IT landscape, and processes, without affecting other parts. Reusing existing functionality (services) makes sure that it can be changed quickly because you don't have to start from scratch every time, and also makes it cheaper. Reuse is also important for companies that aim for operational excellence. Finally, the quality of the data is easier to control, because we can appoint specific services with the responsibility of maintaining the data and enforcing the business rules.