Venturing into the world of Play

Play's installation is hassle free. If you have Java JDK 6 or a later version, all you need to do to get Play working is an installation of Typesafe Activator or Simple Build Tool (SBT).

Play is fully RESTful! Representational State Transfer (REST) is an architectural style, which relies on a stateless, client-server, and cache-enabled communication protocol. It's a lightweight alternative to mechanisms such as Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) and web services (which include SOAP, WSDL, and so on). Here stateless means that the client state data is not stored on the server and every request should include all the data required for the server to process it successfully. The server does not rely on previous data to process the current request. The clients store their session state and the servers can service many more clients in a stateless fashion. The Play build system uses Simple Build Tool (SBT), which is a build tool used for Scala and Java. It also has a plugin to allow native compilation of C and C++. SBT uses incremental recompilation to reduce the compilation time and can be run in triggered execution mode, which means that if specified by the user, required tasks will be run whenever the user saves changes in any of the source files. This feature in particular has been leveraged by the Play Framework so that developers need not redeploy after every change in development stage. This means that if a Play app is running from source on your local machine and you edit its code, you can view the updated app just by reloading the app in the browser.

It provides a default test framework along with helpers and application stubs to simplify both unit and functional testing of the application. Specs2 is the default testing framework used in Play.

Play comes with a Scala-based template engine, due to which it is possible to use Scala objects (String, List, Map, Int, user-defined objects, and so on) in the templates. This was not possible prior to 2.0 because earlier versions of Play relied on Groovy for the template engine.

It uses JBoss Netty as the default web server but any Play 2 application can be packaged as a WAR file and deployed on Servlet 2.5, 3.0, and 3.1 containers, if required. There is a plugin called play2-war-plugin (it can be found at https://github.com/play2war/play2-war-plugin/), which can be used to generate the WAR file for any given Play2 app.

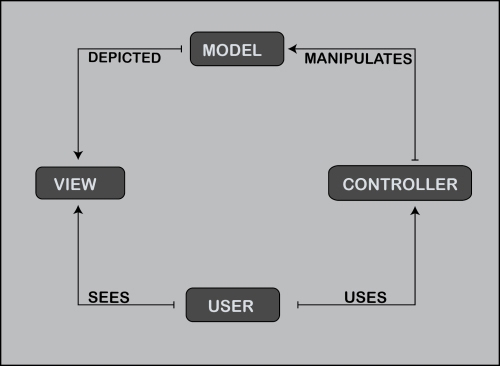

Play endorses the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern. According to the MVC pattern, the components of an application can be divided into three categories:

- Model: This represents application data or activity

- View: This is the part of the application which is visible to the end user

- Controller: This is responsible for processing input from the end user

The pattern also defines how these components are supposed to interact with one another. Let's consider an online store as our application. In this case, the products, brands, users, cart, and so on can be represented by a model each. The pages in the application where users can view the products are defined in the views (HTML pages). When a user adds a product to the cart, the transaction is handled by a controller. The view is unaware of the model and the model is unaware of the view. The controller sends commands to the model and view. The following figure shows how the models, views, and controllers interact:

Play also comes prepackaged with an easy to use Hibernate layer, and offers OpenID, Ehcache, and web service integration straight out of the box by adding a dependency on the individual modules.

In the following sections of this chapter, we'll make a simple app using Play. This is mainly for developers who are using Play earlier.

A sample Play app

There are two ways of creating a new Play application: Activator, and without using Activator. It is simpler to create a Play project using Activator since the most minimalist app would require at least six files.

Typesafe Activator is a tool that can be used to create applications using the Typesafe stack. It relies on using predefined templates to create new projects. The instructions for setting up Activator can be found at http://typesafe.com/get-started.

Building a Play application using Activator

Let's build a new Play application using Activator and a simple template:

$ activator new pathtoNewApp/sampleApp just-play-scala

Then, run the project using the run command:

sampleApp $ sbt run

This starts the application, which is accessible at http://localhost:9000, by default.

Note

The run command starts the project in development mode. In this mode, the source code of the application is watched for changes, and if there are any changes the code is recompiled. We can then make changes to the models, views, or controllers and see them reflected in the application by reloading the browser.

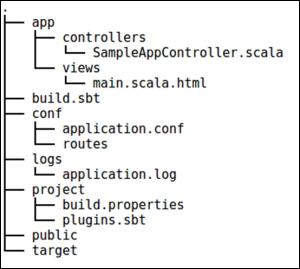

Take a look at the project structure. It will be similar to the one shown here:

If we can't use Activator, we will probably have to create all these files. Now, let's dig into the files individually and see which is for what purpose.

The build definition

Let's start with the crucial part of the project—its build definition, and in our case, the build.sbt file. The .sbt extension comes from the build tool used for Play applications. We will go through the key concepts of this for anyone who isn't familiar with SBT. The build definition is essentially a list of keys and their corresponding values, more or less like assignment statements with the := symbol acting as the assignment operator.

Note

SBT version lower than 0.13.7 expects a new line as the delimiter between two different statements in the build definition.

The contents of the build file are:

name := "sampleApp"""

version := "1.0.0"

lazy val root = project.in(file(".")).enablePlugins(PlayScala)In the preceding build definition, the values for the project's name, version, and root are specified. Another way of specifying values is by updating the existing ones. We can append to the existing values using the += symbol for individual items and ++= for sequences. For example:

resolvers += Resolver.sonatypeRepo("snapshots")

scalacOptions ++= Seq("-feature", "-language:reflectiveCalls")

resolvers is the list of URLs from where the dependencies can be picked up and scalacOptions is the list of parameters passed to the Scala compiler.

Alternatively, an SBT project can also use a .scala build file. The structure for our application would then be:

The .scala build definition for SimpleApp will be:

import sbt._

import Keys._

import play.Play.autoImport._

import PlayKeys._

object ApplicationBuild extends Build {

val appName = "SimpleApp"

val appVersion = "1.0.0"

val appDependencies = Seq(

// Add your project dependencies here

)

val main = Project(appName, file(".")).enablePlugins(play.PlayScala).settings(

version := appVersion,

libraryDependencies ++= appDependencies

)

}The .scala build definition comes in handy when we need to define custom tasks/settings for our application/plugin, since it uses Scala code. The .sbt definition is generally smaller and simpler than its corresponding .scala definition and is hence, more preferred.

Without the Play settings, which are imported by enabling the PlayScala plugin, SBT is clueless that our project is a Play application and is defined according to the semantics of a Play application.

So, is that statement sufficient for SBT to run a Play app correctly?

No, there is something else as well! SBT allows us to extend build definitions using plugins. Play-based projects make use of the Play SBT plugin and it is from this plugin that SBT gets the required settings. In order for SBT to download all the plugins that our project will be using, they should be added explicitly. This is done by adding them in plugins.sbt in the projectRoot/project directory.

Let's take a look at the plugins.sbt file. The file content will be:

resolvers += "Typesafe repository" at "http://repo.typesafe.com/typesafe/releases/"

addSbtPlugin("com.typesafe.play" % "sbt-plugin" % "2.3.8")The parameter passed to addSbtPlugin is the Ivy module ID for the plugin. The resolver is helpful when the plugin is not hosted on Maven or Typesafe repositories.

The build.properties file is used to specify the SBT version to avoid incompatibility issues between the same build definitions compiled by using two or more different versions of SBT.

This covers all the build-related files of a Play application.

The source code

Now, let us look at the source code for our project. Most of the source is in the app folder. Generally, the model's code is within app/models or app/com/projectName/models and the controller's source code is in app/co

ntrollers or app/com/projectName/controllers, where com.projectName is the package. The code for the views should be in app/views or within a subfolder in app/views.

The views/main.scala.html file is the page we will be able to see when we run our application. If this file is missing, you can add it. If you are wondering why the file is named main.scala.html and not main.html, this is because it's a Twirl template; it facilitates using Scala code along with HTML to define views. We will delve deeper into this in Chapter 4, Exploring Views.

Now, update the content of main.scala.html to:

@(title: String)(content: Html)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>@title</title>

</head>

<body>

@content

</body>

</html>We can provide the title and content from our Scala code to display this view. A view can be bound to a specific request through the controllers. So, let's update the code for our controller SampleAppController, as follows:

package controllers

import play.api.mvc._

import play.api.templates.Html

object SampleAppController extends Controller {

def index = Action {

val content = Html("<div>This is the content for the sample app<div>")

Ok(views.html.main("Home")(content))

}

}Tip

Downloading the example code

You can download the example code files for all Packt books you have purchased from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Action and Ok are methods made available by the play.mvc.api package. Chapter 2, Defining Actions covers them in detail.

On saving the changes and running the application, we will see the page hosted at http://localhost:9000, as shown in the screenshot:

Request handling process

Let's see how the request was handled!

All requests that will be supported by the application must be defined in the conf/routes file. Each route definition has three parts. The first part is the request method. It can be any one of GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE. The second part is the path and the third is the method, which returns a response. When a request is defined in the conf/routes file, the method to which it is mapped in the conf/routes file is called.

For example, an entry in the routes file would be:

GET / controllers.SampleAppController.index

This means that for a GET request on the / path, we have mapped the response to be the one returned from the SampleController.index() method.

A sample request would be:

curl 'http://localhost:9000/'

Go ahead and add a few more pages to the application to get more comfortable, maybe a FAQ, Contact Us, or About.

The request-response cycle for a Play app, explained in the preceding code is represented here:

The public directory is essentially used to serve resources, such as stylesheets, JavaScript, and images that are independent of Play. To make these files accessible, the path to public is also added in routes by default:

GET /assets/*file controllers.Assets.at(path="/public", file)

We will see routes in detail in Chapter 3, Building Routes.

The file conf/application.conf is used to set application-level configuration properties.

The target directory is used by SBT for the files generated during compile, build, or other processes.

Creating a TaskTracker application

Let us create a simple

TaskTracker application, which allows us to add pending tasks and delete them. We will continue by modifying SampleApp, built in the previous section. In this app, we will not be using a DB to store the tasks. It is possible to persist models in Play using Anorm or other modules; this is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5, Working with Data.

We need a view that has an input box to enter the task. Add another template file, index.scala.html, to the views, using the template generated in the preceding section as boilerplate:

@main("Task Tracker") {

<h2>Task Tracker</h2>

<div>

<form>

<input type="text" name="taskName" placeholder="Add a new Task" required>

<input type="submit" value="Add">

</form>

</div>

}In order to use a template, we can call its generated method from our Scala code or refer to it in other templates by using its name. Using a main template can come in handy when we want to apply a change to all the templates. For example, if we want to add a style sheet for an application, just adding this in our main template will ensure that it's added for all the dependent views.

To view this template's content on loading, update the index method to:

package controllers

import play.api.mvc._

object TaskController extends Controller {

def index = Action {

Ok(views.html.index())

}

}Notice that we have also replaced all occurrences of SampleAppController to TaskController.

Run the application and view it in the browser; the page will look similar to this figure:

Now, in order to work on the functionality, let's add a model called Task, which we'll use to represent the task in our app. Since we want to delete the functionality too, we will need to identify each task using a unique ID, which means that our model should have two properties: an ID and a name. The Task model will be:

package models

case class Task(id: Int, name: String)

object Task {

private var taskList: List[Task] = List()

def all: List[Task] = {

taskList

}

def add(taskName: String) = {

val newId: Int = taskList.last.id + 1

taskList = taskList ++ List(Task(newId, taskName))

}

def delete(taskId: Int) = {

taskList = taskList.filterNot(task => task.id == taskId)

}

}In this model, we are using a taskList private variable to keep track of the tasks for the session.

In the add method, whenever a new task is added, we append it to this list. Instead of keeping another variable to keep count of the IDs, I choose to increment the ID of the last element in the list.

In the delete method, we simply filter out the task with the given ID and the all method returns the list for this session.

Now, we need to call these methods in our controller and then bind them to a request route. Now, update the controller in this way:

import models.Task

import play.api.mvc._

object TaskController extends Controller {

def index = Action {

Redirect(routes.TaskController.tasks)

}

def tasks = Action {

Ok(views.html.index(Task.all))

}

def newTask = Action(parse.urlFormEncoded) {

implicit request =>

Task.add(request.body.get("taskName").get.head)

Redirect(routes.TaskController.index)

}

def deleteTask(id: Int) = Action {

Task.delete(id)

Ok

}

}In the preceding code, routes refers to the helper that can be used to access the routes defined for the application in

conf/routes. Try running the app now!

It'll throw a compilation error, which says that values tasks is not a member of controllers.ReverseTaskController. This occurs because we haven't yet updated the routes.

Adding a new task

Now, let's bind actions to get tasks and add a new task:

GET / controllers.TaskController.index # Tasks GET /tasks controllers.TaskController.tasks POST /tasks controllers.TaskController.newTask

We'll complete our application's view so that it can facilitate the following:

accept and render a List[Task]

@(tasks: List[Task])

@main("Task Tracker") {

<h2>Task Tracker</h2>

<div>

<form action="@routes.TaskController.newTask()" method="post">

<input type="text" name="taskName" placeholder="Add a new Task" required>

<input type="submit" value="Add">

</form>

</div>

<div>

<ul>

@tasks.map { task =>

<li>

@task.name

</li>

}

</ul>

</div>

}We have now added a form in the view, which takes a text input with the taskName name and submits this data to a TaskController.newTask method.

Note

Notice that we have now added a tasks argument for this template and are displaying it in the view. Scala elements and predefined templates are prepended with the @ twirl symbol in the views.

Now, when running the app, we will be able to add tasks as well as view existing ones, as shown here:

Deleting a task

The only thing remaining in our app is the ability to delete a task. Update the index template so that each <li> element has a button, whose click results in a delete request to the server:

<li>

@task.name <button onclick="deleteTask ( @task.id) ;">Remove</button>

</li>Then, we would need to update the routes file to map the delete action:

DELETE /tasks/:id controllers.TaskController.deleteTask (id: Int).

We also need to define deleteTask in our view. To do this, we can simply add a script:

<script>

function deleteTask ( id ) {

var req = new XMLHttpRequest ( ) ;

req.open ( "delete", "/tasks/" + id ) ;

req.onload = function ( e ) {

if ( req.status = 200 ) {

document.location.reload ( true ) ;

}

} ;

req.send ( ) ;

}

</script>Note

Ideally, we shouldn't be defining JavaScript methods in the window's global namespace. It has been done in this example, so as to keep it simple and it's not advised for any real-time application.

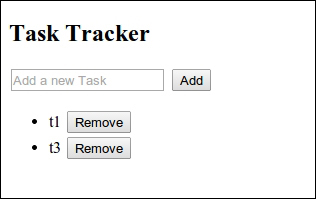

Now, when we run the app, we can add tasks as well as remove them, as shown here:

I am leaving the task of beautifying the app up to you. Add a style sheet in the public directory and declare it in the main template. For example, if the taskTracker.css file is located at public/stylesheets, the link to it in the main.scala.html file would be:

<link rel="stylesheet" media="screen" href="@routes.Assets.at("stylesheets/taskTracker.css")">