Examining the incumbent’s external and internal context at a glance

When understanding the conditions and circumstances under which the incumbent operates, it is important to examine the financial services industry’s external and internal environments, seen from the perspective of our main actor. Getting this contextual understanding will serve as a fundamental awareness element for the rest of the book, especially when relating the industry’s context with that of DevOps. Context is of vital importance in adopting DevOps, as we will also see later in the book, and the financial services context is indeed evolving at a very dynamic pace.

What does an incumbent bank’s external context look like?

The term external context is used to refer to the external environment within which the bank operates. As our bank operates in global markets, we are taking a global average and as representative as possible a snapshot, while of course, we remain conscious that factors such as specific regions, countries, market conditions, regulatory frameworks, and economic factors force our bank to be faced in its reality with more dynamic and versatile circumstances and conditions than our snapshot presents.

As this is not an economics book, we will refrain from discussing economic concepts such as interest rates, inflation, gross domestic product, and industrial production indexes when examining the external environment. We will exclusively focus on the external environmental factors that do have a direct and/or indirect relation to how our incumbent’s DevOps enterprise adoption will be designed and will evolve.

Regulatory focus due to the 2008 financial crisis

Let’s attempt a flashback and go back to the years after 2008 and the global financial crisis. The aftermath of the crisis for large incumbent banks was characterized by waves of heavy regulatory requirements (Basel, EMIR, MiFID, Dodd-Frank, PSD, SCI, and T2S, to mention a few), which were complemented by extremely rigorous audit assessments, especially for globally systemically important institutions. Those audit assessments, apart from traditionally assessing the compliance and maturity levels of business operations, activities, and resiliency, were complemented by a significant focus on IT infrastructure and the related service domain. Technology operations and IT risk management came into strong focus with the supervisory authorities somewhere around 2015. By coincidence, around that time was the period that DevOps started to be known as a concept in the industry.

Licenses to operate came at risk, and capital was set aside to cover potential fines due to foreseeable challenges in complying with legislation on time. Inevitably, that situation forced incumbent banks to deploy significant amounts of their capital and resources to regulatory work, while in parallel they were struggling with profitability due to the volatile macroeconomic conditions of that period. Digital innovation agendas were compromised or put on hold for some time.

Obviously, the circumstances did not totally hold incumbents back from innovating during those years. Some indeed took advantage of the regulatory demand and capital set aside for those purposes to promote their digital innovation agendas, which was an intelligent tactic indeed. To some extent, it was also inevitable to not invest in new technologies, in order to close old audit remarks, as new regulations could not be met with legacy applications, infrastructure, and tools. Therefore, deploying innovative technologies to effectively respond to the continuously evolving regulatory environment, in certain cases, was the only sustainable way. Nevertheless, despite the creative mindset and approaches of several incumbent banks, their digital innovation plans were jeopardized, or at least slowed down.

Technology industrialized rapidly in the meantime

That turbulent period for the industry was at the same time a period of rapid advancement for technological utilities and concepts globally. Technologies such as APIs, cloud services, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data analytics were proliferating and maturing, while concepts such as enterprise agility, DevOps, and SRE created new means and enablers for digital innovation and new ways of working (WoW) in the industry. Digital services have become mainstream in recent years, hybrid cloud has become the dominant infrastructure model, cyber security is evolving on top of the risk factors agenda, regulators are becoming more tech-savvy, the challenger banks’ business model delivers, and investment in digital customer journeys and intelligence has become one of the top profitability sources. The adaptation of such technologies and concepts challenges the traditional technology operating models of incumbents, requiring a generous shift toward modern WoW and advanced engineering capabilities. Concepts that the industry used to call “another nice thing to have” have become “another necessary capability we need to build.”

In recent years, and after that decade of global economic volatility and high focus on responding to regulatory demand, incumbents have entered an era of financial growth, characterized by increased profitability, which, in combination with technological advancements, allows capital and resources to be strategically deployed on digital innovation, materializing what some in the industry call the long-awaited transformation. Technology has started not only to be considered a key business enabler but the business itself.

Which are the forces that shape the financial services industry?

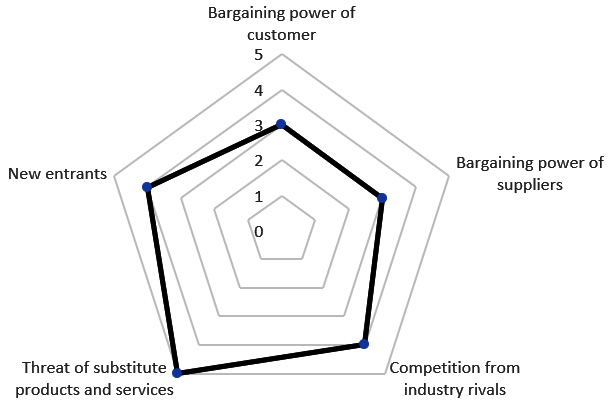

On providing a more detailed and rounded picture of the incumbent’s external environment, Porter’s Five Forces model is used to identify and analyze the industry’s main five competitive forces and reveal its respective strengths and weaknesses. The results of this method can be used by companies to support the evolution of their corporate strategy, which influences their technology strategy and consequently their DevOps adoption, as we will discuss in the next chapter.

A representative Five Forces analysis of our incumbent bank is presented as follows:

- Bargaining power of customers – Pressure level: Moderate: This force is very much client segment dependent, as well as operating markets and business domain related. A small daily banking client holding a bank account with a deposit of 1,000 euros has close to zero purchasing power if they decide to move to another bank. In contrast, a wealthy private or corporate banking client with a diversified portfolio of assets with a value of 500 million euros has significant purchasing power, as they could cause financial and reputational loss. The former is the one who is most likely to leave our incumbent for a challenger or neobank and the latter to another incumbent.

- Bargaining power of suppliers – Pressure level: Moderate: The two major suppliers of an incumbent bank are capital and people. The ability of the bank to compete in its markets, generate strong revenue, and maintain a high credit score rating, as well as meeting its return of equity and cost/income ratio targets, can attract clients and investors. Nevertheless, even though incumbents have returned to strong profitability, presently corporate investors’ interest in expanding their investments beyond incumbents toward challengers through funding rounds is increasing. On the people side, technological advancements, people skill scarcity in the market, talent competition, as well as the new flexible working conditions brought about by the Covid pandemic increase the challenge of maintaining and hiring talented people, primarily in technological domains. In addition, challengers and neobanks look appealing in the eyes of young talent, due to better career prospects through the usage of the latest technologies.

- Competition from industry rivals – Pressure level: High: The industry is traditionally very competitive, driven by aggressive profitability targets and ratios, backed by a digitalization time-to-market race for new products and services. The relatively low cost of switching from one incumbent to another or from an incumbent to a challenger intensifies an already competitive landscape. This rivalry, though, apart from bringing competition, also generates opportunities for joint ventures. The motto if you can’t beat them, join them is becoming part of corporate strategies across the industry and domain-specific ecosystems, through increased merger and acquisition (M&A) activities, vertical integrations, and FinTech incubation hubs. Banco Santander is a great example of an incumbent that is very active in pursuing joint ventures.

- Threat of substitute products and services – Pressure level: High: The incumbent’s monopoly is undoubtedly in decline. The industry is threatened by substitutions arising from the proliferation of new players within its ecosystem (challengers, neobanks, and infrastructure providers), as well as technological giants such as Google and Apple (in association with incumbents such as Goldman Sachs) that have entered the financial services industry. Changing customer behaviors, which is driven by the high technological literacy of new generations on one hand and on the other hand by sharing economic factors, generate demand for new substitute services. As the COO of a bank, I used to work on the basis of the saying Most customers now have smartphones and many options. What they do not have is time and patience. However, a competitive advantage that incumbents still maintain is that they offer the most complete service and product offerings across financial services domains, including financial advice.

- New entrants – Pressure level: High: The new entrants, after an initial period of facing high obstacles to penetrate the market and compete with incumbents, due to certain entry barriers such as regulatory frameworks, capital and license requirements, legacy bonds of clients with traditional institutions, and reputation establishment, have eventually made a significant breakthrough in the industry. Many of these new entrants have managed to build trust in the industry’s clients and attract funds from investors, as well as talented people. Their advantage is not only fully digital services, with reduced costs, but also new business models, improved customer experience, and technology service reliability. The effect that new entrants have varies across operating markets, business domains, and ecosystems, primarily due to factors such as regulatory frameworks, the resiliency and robustness of incumbents, as well as their market position, along with customer relations and behaviors.

Figure 1.1 – Porter’s Five Forces (1979) adapted to the financial services industry

What does an incumbent’s internal context look like?

The internal context of our representative incumbent bank is subject to more differences per incumbent compared to the external context, one can argue. There are, though, certain commonalities characterizing the internal context of globally and regionally systemically important banks. As we did with the external context, we will not cover the complete spectrum of internal conditions and will focus only on internal forces that have a direct or indirect foreseeable impact on enterprise DevOps adoption.

Persistent pressure on cost/income ratio

Incumbent banks, to remain competitive, need to continuously improve their cost/income ratio. This can either be achieved by reducing operating costs while keeping revenue relatively flat, or by keeping operating costs relatively flat and increasing revenue, or the happy days scenario, which combines operating cost reduction and revenue increase in parallel. Obviously, there is a convenient solution available, which is to bravely reduce the operating costs of the bank, as revenue increase is an exercise that requires great effort, and it is also affected by several external factors. In addition, focusing primarily on operating cost reduction can have an immediate effect on the bank’s balance sheet, while revenue increase is more of a long-term impact. Therefore, incumbents are extremely cost-conscious.

Bonus Information

The cost/income ratio is a major metric that determines the profitability of a bank. Its measurement analyzes the operating costs of running the bank against its operating income. The lower the cost/income, the more efficient and profitable a bank is. The mathematical formula used is operating cost / operating income = cost/income ratio.

Operational efficiency focus

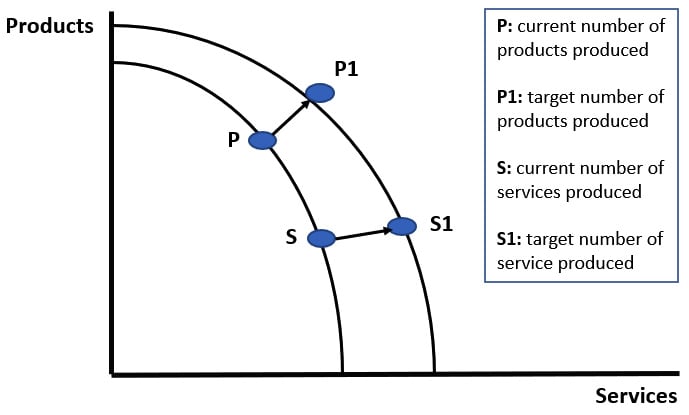

Incumbents strive to produce more with less in improving their operational efficiency through the utilization of resources. Aiming to maintain a competitive advantage and create a first-mover advantage through the delivery of more innovative services and products, incumbents continuously examine possibilities to extend their production possibilities frontier through resource utilization. Their production possibilities frontier can be increased either with extra people and capital deployed, which is not the ideal strategy due to cost constraints, as we explained earlier, or by deploying technological advancements as their means of delivering new products and services. The latter sounds optimal and is the only sustainable possibility. In distinguishing this internal context factor from the cost-income ratio factor, we need to clarify that producing more does not necessarily mean more revenue, and the deployment of new technologies will also not necessarily come with a cost reduction in technology operating expenses. Your new products might not sell, and the utilization of new technologies does not come for free.

Figure 1.2 – Production possibilities frontier, adapted to incumbent banks

New ways of working

New, in this case, does not mean newly invented in the industry, but new in the sense of enabling new ways of doing things in a banking context. Concepts such as Agile, DevOps, scaled Agile delivery, modern software delivery, and site reliability engineering have been around for many years but very few incumbents have found solid steps in adopting them in a harmonious and scaled way, characterized by continuous organic evolution and not back-to-back transformation programs. You will often hear stories such as Bank A just started its Agile Transformation v3 or that Bank B started its DevOps Industrialization v2. I always remember a saying from an ex-peer of mine: Banks get transformation programs done so they can start another transformation program to transform the results of the previous one. This is of course not representative of every incumbent, but it does hold lots of truth in it. Another present challenge is the difficulty for incumbents to fit all the new WoW concepts under one operating model that is characterized by harmony and reconciliation. Often, also, as we will see later in the book, the adoption of new WoW concepts is complemented by organization structure changes that in many cases defeat the new WoW method’s purpose. All of this results in a confused and misaligned modus operandi, characterized by internal variations, an ineffective blend of old and new ways of doing things, and resistance, under the mentality that if it is not invented here, it cannot be implemented here.

Organizational debt

In IT, we often use the term technical debt, referring to software solutions that have been deployed to production that are characterized by low quality and in the future will result in functional and non-function abnormalities. Looking at the broader context, incumbents are faced with what I prefer to call organizational debt, which spans horizontally and vertically across their organizations, from outdated people skills to coupled legacy platforms, and from bureaucratic policies to complex and cumbersome manual processes, backed by a deep-rooted old-school mentality on WoW, based on silos and fragmentation. All these elements have multidimensional and domino-effect consequences for an incumbent’s internal operations and its ability to transform and advance. Such conditions not only increase the cost and complexity of delivering and running technological solutions but also impose high operational and regulatory risk, slow down the adoption of new WoW and radical digitalization initiatives, as well as impose a great risk on an incumbent’s ability to attract and maintain talented people.

Digitalization and platformization

Banking as a service is becoming the new business model norm and a vehicle for staying relevant, enabled by significant investment in digitalization and platformization. The focus is not only narrowed on how clients interact with banks but also on how internal business units interact with IT, as well as IT-to-IT interaction. However, in many cases, banks face significant challenges on that digitalization and platformization journey, primarily due to heavy reliance on legacy technological platforms. The situation is characterized by old untenable platforms, with unknown technical debt, black-box business logic implementations, expiring maintenance contracts, poor documentation, monolithic architectures, lack of integration, high customization, difficulty upgrading, unreliability, and scarcity of people with deep knowledge. What is often called in the industry a legacy dilemma is still to be solved for most incumbents, with some bombs ticking as we speak (borrowing an expression of an ex-CIO of mine).

Corporate and technology strategy objective misalignment

Technology is there to enable the business and the other way around, you could rightly claim. That statement indicates that corporate and technology strategies need to therefore be in close alignment and evolve together. This condition of alignment is challenging to achieve, especially in very large incumbents. Organizational structures, siloed business domain thinking, a lack of collective strategic initiatives, conflicting performance indicators, ambiguous benefit realization procedures, a lack of technological literacy on the business side, as well as a lack of business literacy on the technological side, in combination with middle management being the transmitter of priorities and direction, creates a condition of misalignment and misunderstandings. On the technological side, this misalignment in many cases goes deeper between the business IT areas and the core infrastructure teams. One of the situation’s consequences is the occurrence of extreme variations in the adoption of different technologies and concepts. Another consequence is the inability of teams to understand how they are supposed to contribute to materializing the incumbent’s strategic objectives, the motivation behind those objectives, as well as what their position is and their role in the delivery value stream.