Using React to build UIs means that we can declare the structure of the UI with JSX. This is less error-prone than the imperative approach of assembling the UI piece by piece. However, the declarative approach does present a challenge: performance.

For example, having a declarative UI structure is fine for the initial rendering, because there's nothing on the page yet. So, the React renderer can look at the structure declared in JSX and render it in the DOM browser.

The Document Object Model (DOM) represents HTML in the browser after it has been rendered. The DOM API is how JavaScript is able to change content on the page.

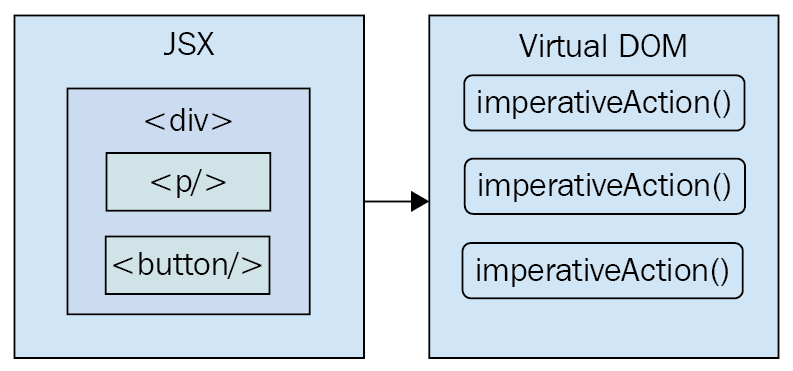

This concept is illustrated in the following diagram:

On the initial render, React components and their JSX are no different from other template libraries. For instance, Handlebars will render a template to HTML markup as a string, which is then inserted into the browser DOM. Where React is different from libraries such as Handlebars is when data changes and we need to re-render the component. Handlebars will just rebuild the entire HTML string, the same way it did on the initial render. Since this is problematic for performance, we often end up implementing imperative workarounds that manually update tiny bits of the DOM. We end up with a tangled mess of declarative templates and imperative code to handle the dynamic aspects of the UI.

We don't do this in React. This is what sets React apart from other view libraries. Components are declarative for the initial render, and they stay this way even as they're re-rendered. It's what React does under the hood that makes re-rendering declarative UI structures possible.

React has something called the virtual DOM, which is used to keep a representation of the real DOM elements in memory. It does this so that each time we re-render a component, it can compare the new content to the content that's already displayed on the page. Based on the difference, the virtual DOM can execute the imperative steps necessary to make the changes. So, not only do we get to keep our declarative code when we need to update the UI, but React will also make sure that it's done in a performant way. Here's what this process looks like:

When you read about React, you'll often see words such as diffing and patching. Diffing means comparing old content with new content to figure out what's changed. Patching means executing the necessary DOM operations to render the new content.

Like any other JavaScript library, React is constrained by the run-to-completion nature of the main thread. For example, if the React internals are busy diffing content and patching the DOM, the browser can't respond to user input. As you'll see in the last section of this chapter, changes were made to the internal rendering algorithms in React 16 to mitigate these performance pitfalls.

With performance concerns addressed, we need to make sure that we're confident that React is flexible enough to adapt to different platforms that we might want to deploy our apps to in the future.

United States

United States

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

India

India

Germany

Germany

France

France

Canada

Canada

Russia

Russia

Spain

Spain

Brazil

Brazil

Australia

Australia

Argentina

Argentina

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Chile

Chile

Colombia

Colombia

Cyprus

Cyprus

Czechia

Czechia

Denmark

Denmark

Ecuador

Ecuador

Egypt

Egypt

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Indonesia

Indonesia

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Japan

Japan

Latvia

Latvia

Lithuania

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Malaysia

Malaysia

Malta

Malta

Mexico

Mexico

Netherlands

Netherlands

New Zealand

New Zealand

Norway

Norway

Philippines

Philippines

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Romania

Romania

Singapore

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Slovenia

South Africa

South Africa

South Korea

South Korea

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland

Taiwan

Taiwan

Thailand

Thailand

Turkey

Turkey

Ukraine

Ukraine