SRE's evolution; technical and cultural practices

This section tracks back the evolution of SRE, defines SRE, discusses how SRE relates to DevOps by elaborating DevOps key pillars, details critical jargon, and introduces SRE's cultural practices.

The evolution of SRE

In the early 2000s, Google was building massive, complex systems to run their search and other critical services. Their main challenge was to reliably run their services. At the time, many companies historically had system administrators deploying software components as a service. The use of system administrators, otherwise known as the sysadmin approach, essentially focused on running the service by responding to events or updates as they occur. This means that if the service grew in traffic or complexity, there would be a corresponding increase in events and updates.

The sysadmin approach has its pitfalls, and these are represented by two categories of cost:

- Direct costs: Running a service with a team of system administrators included manual intervention. Manual intervention at scale is a major downside to change management and event handling. However, this manual approach was adopted by multiple organizations because there wasn't a recognized alternative

- Indirect costs: System administrators and developers widely differed in terms of their skills, the vocabulary used to describe situations, and incentives. Development teams always want to launch new features and their incentive is to drive adoption. System administrators or ops teams want to ensure that the service is running reliably and often with a thought process of don't change something that is working.

Google did not want to pursue a manual approach because at their scale and traffic, any increase in demand would make it impractical to scale. The desire to regularly push more features to their users would ultimately cause conflict between developers and operators. Google wanted to reduce this conflict and remove the confusion with respect to desired outcomes. With this knowledge, Google considered an alternative approach. This new approach is what became known as SRE.

Understanding SRE

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

The preceding is a quote from Ben Treynor Sloss, who in 2003 started the first SRE team at Google with seven software engineers. Ben himself was a software engineer up until that point, and joined Google as the site reliability Tsar in 2003, led the development and operations of Google's production software infrastructure, network, and user-facing services, and is currently the VP of engineering at Google. At that point in 2003, neither Ben nor Google had any formal definition for SRE.

SRE is a software engineering approach to IT operations. SRE is an intrinsic part of Google's culture. It's the key to running their massively complex systems and services at scale. At its core, the goal of SRE is to end the age-old battle between development and operations. This section introduces SRE's thought process and the upcoming chapters on SRE give deeper insights into how SRE achieves its goal.

A primary difference in Google's approach to building the SRE practice or team is the composition of the SRE team. A typical SRE team consists of 50-60% Google software engineers. The other 40-50% are personnel who have software engineering skills but in addition, also have skills related to UNIX/Linux system internals and networking expertise. The team composition forced two behavioral patterns that propelled the team forward:

- Team members were quickly bored of performing tasks or responding to events manually.

- Team members had the capability to write software and provide an engineering solution to avoid repetitive manual work even if the solution is complicated.

In simple terminology, SRE practices evolved when a team of software engineers ran a service reliably in production and automated systems by using engineering practices. This raises some critical questions. How is SRE different from DevOps? Which is better? This will be covered in the upcoming sub-sections.

From Google's viewpoint, DevOps is a philosophy rather than a development methodology. It aims to close the gap between software development and software operations. DevOps' key pillars clarify what needs to be done to achieve collaboration, cohesiveness, flexibility, reliability, and consistency.

SRE's approach toward DevOps' key pillars

DevOps doesn't put forward a clear path or mechanism for how it needs to be done. Google's SRE approach is a concrete or prescriptive way to solve problems that the DevOps philosophy addresses. Google describes the relationship between SRE and DevOps using an analogy:

(Google Cloud, SRE vs. DevOps: competing standards or close friends?, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/gcp/sre-vs-devops-competing-standards-or-close-friends)

Let's look at how SRE implements DevOps and approaches the DevOps key pillars:

- Reduces organizational silos: SRE reduces organizational silos by sharing ownership between developers and operators. Both teams are involved in the product/service life cycle from the start. Together they define Service-Level Objectives (SLOs), Service-Level Indicators (SLIs), and error budgets and share the responsibility to determine the reliability, work priority, and release cadence of new features. This promotes a shared vision and improves communication and collaboration.

- Accepts failure as normal: SRE accepts failure as normal by conducting blameless postmortems, which includes detailed analysis without any reference to a person. Blameless postmortems help to understand the reasons for failure, identifying preventive actions, and ensuring that a failure for the same reason doesn't re-occur. The goal is to identify the root cause and process but not to focus on individuals. This helps to promote psychological safety. In most cases, failure is the result of a missing SLO or targets and incidents are tracked using specific indicators as a function of time or SLI.

- Implements gradual change: SRE implements gradual changes by limited canary rollouts and eventually reduces the cost of failures. Canary rollouts refer to the process of rolling out changes to a small percentage of users in production before making them generally available. This ensures that the impact is limited to a small set of users and gives us the opportunity to capture feedback on the new rollouts.

- Leverages tooling and automation: SRE leverages tooling and automation to reduce toil or the amount of manual repetitive work, and it eventually promotes speed and consistency. Automation is a force multiplier. However, this can create a lot of resistance to change. SRE recommends handling this resistance to change by understanding the psychology of change.

- Measures everything: SRE promotes data-driven decision making, encourages goal setting by measuring and monitoring critical factors tied to the health and reliability of the system. SRE also measures the amount of manual, repetitive work spent. Measuring everything is key for setting up SLOs and Service-Level Agreements (SLAs) and reducing toil.

This wraps up our introduction to SRE's approach to DevOps key pillars; we referred to jargon such as SLI, SLO, SLA, error budget, toil, and canary rollouts. These will be introduced in the next sub-section.

Introducing SRE's key concepts

SRE implements the DevOps philosophy via several key concepts, such as SLI, SLO, SLA, error budget, and toil.

Becoming familiar with SLI, SLO, and SLA

Before diving into the definitions of SRE terminology – specifically SLI, SLO, and SLA – this sub-section attempts to introduce this terminology through a relatable example.

Let's consider that you are a paid consumer for a video streaming service. As a paid consumer, you will have certain expectations from the service. A key aspect of that expectation is that the service needs to be available. This means when you try to access the website of the video streaming service via any permissible means, such as mobile device or desktop, the website needs to be accessible and the service should always work.

If you frequently encounter issues while accessing the service, either because the service is experiencing high traffic or the service provider is adding new features, or for any other reason, you will not be a happy consumer. Now, it is possible that some users can access this service at a moment in time but some users are unable to access it at the same moment in time. Those users who are able to access it are happy users and users who are unable to access it are sad users.

Availability

The first and most critical feature that a service should provide is availability. Service availability can also be referred to as its uptime. Availability is the ability of an application or service to run when needed. If a system is not running, then the system will fail.

Let's assume that you are a happy user. You can access the service. You can create a profile, browse titles, filter titles, watch reviews for specific titles, add videos to your watchlist, play videos, or add reviews to viewed videos. Each of these actions performed by you as a user can be categorized as a user journey. For each user journey, you will have certain expectations:

- If you try to browse titles under a specific category, say comedy, you would expect that the service loads the titles without any delay.

- If you select a title that you would like to watch, you would expect to watch the video without any buffering.

- If you would like to watch a livestream, you would expect the stream contents to be as fresh as possible.

Let's explore the first expectation. When you as a user tries to browse titles under comedy, how fast is fast enough?

Some users might expect to display the results within 1 second, and some might expect it in 200 ms and some others in 500 ms. So, the expectation needs to be quantifiable and for it to be quantifiable, it needs to be measurable. The expectation should be set to a value where most of the users will be happy. It should also be measured for a specific duration (say 5 minutes) and should be met over a period (say 30 days). It should not be a one-time event. If the expectation is not met over a period users expect, the service provider takes on some accountability and addresses the users' concerns either by issuing a refund or adding extra service credits.

For a service to be reliable, the service needs to have key characteristics based on expectations from user journeys. In this example, the key characteristics that the user expects are latency, throughput, and freshness.

Reliability

Reliability is the ability of an application or service to perform a specific function within a specific time without failures. If a system cannot perform its intended function, then the system will fail.

So, to summarize the example of a video streaming service, as a user you will expect the following:

- The service is available.

- The service is reliable.

Now, let's introduce SRE terminology with respect to the preceding example before going into their formal definitions:

- Expecting the service to be available or expecting the service to meet a specific amount of latency, throughput, or freshness, or any other characteristic that is critical to the user journey, is known as SLI.

- Expecting the service to be available or reliable for a certain target level over a specific period is SLO.

- Expecting the service to meet a pre-defined customer expectation, the failure of which results in a refund or credits, is SLA.

Let's move on from this general understanding of these concepts and explore how Google views them by introducing SRE's technical practices.

SRE's technical practices

SRE specifically prescribes the usage of specific technical tools or practices that will help to define, measure, and track service characteristics such as availability and reliability. These are referred to as SRE technical practices and specifically refer to SLIs, SLOs, SLAs, error budget, and toil. These are introduced in the following sections with significant insights.

Service-Level Indicator (SLI)

Google SRE has the following definition for SLI:

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

Most services consider latency or throughput as key aspects of a service based on related user journeys. SLI is a specific measurement of these aspects where raw data is aggregated or collected over a measurement window and represented as a rate, average, or percentile

Let's now look at the characteristics of SLIs:

- It is a direct measurement of a service performance or behavior.

- Refers to measurable metrics over time.

- Can be aggregated and turned to rate, average, or percentile.

- Used to determine the level of availability. SRE considers availability as the prerequisite to success.

SLI can be represented as a formula:

For systems serving requests over HTTPS, validity is often determined by request parameters such as hostname or requested path to scope the SLI to a particular set of serving tasks, or response handlers. For data processing systems, validity is usually determined by the selection of inputs to scope the SLI to a subset of data. Good events refer to the expectations from the service or system.

Let's look at some examples of SLIs:

- Request latency: The time taken to return a response for a request should be less than 100 ms.

- Failure rate: The ratio of unsuccessful requests to all received requests should be greater than 99%.

- Availability: Refers to the uptime check on whether a service is available or not at a particular point in time.

Service-Level Objective (SLO)

Google SRE uses the following definition for SLO:

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

Customers have specific expectations from a service and these expectations are characterized by specific indicators or SLIs that are tailored per the user journey. SLOs are a way to measure customer happiness and their expectations by ensuring that the SLIs are consistently met and are potentially reported before the customer notices an issue.

Let's now look at the characteristics of SLOs:

- Identifies whether a service is reliable enough.

- Directly tied to SLIs. SLOs are in fact measured by using SLIs.

- Can either be a single target or a range of values for the collection of SLIs.

- If the SLI refers to metrics over time, which details the health of a service, then SLOs are agreed-upon bounds on how often the SLIs must be met.

Let's see how they are represented as a formula:

target OR

target OR

SLO can best be represented either as a specific target value or as a range of values for an SLI for a specific aspect of a service, such as latency or throughput, representing the acceptable lower bound and possible upper bound that is valid over a specific period. Given that SLIs are used to measure SLOs, SLIs should be within the target or between the range of acceptable values

Let's look at some examples of SLOs:

- Request latency: 99.99% of all requests should be served under 100 ms over a period of 1 month or 99.9% of all requests should be served between 75 ms and 125 ms for a period of 1 month.

- Failure rate: 99.9% of all requests should have a failure rate of 99% over 1 year.

- Availability: The application should be usable for 99.95% of the time over 24 hours.

Service-Level Agreement (SLA)

Google SRE uses the following definition for SLAs:

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

An SLA is an external-facing agreement that is provided to the consumer of a service. The agreement clearly lays out the minimum expectations that the consumer can expect from the service and calls out the consequences that the service provider needs to face if found in violation. The consequences are generally applied in terms of refund or additional credits to the service consumer.

Let's now look at the characteristics of SLAs:

- SLAs are based on SLOs.

- Signifies the business factor that binds the customer and service provider.

- Represents the consequences of what happens when availability or customer expectation fails.

- Are more lenient than SLOs to trigger early alarms as these are the minimum expectations that the service should meet.

SLAs' priority in comparison to SLOs can be represented as follows:

Let's look at some examples of SLAs:

- Latency: 99% of all requests per day should be served under 150 ms; otherwise, 10% of the daily subscription fee will be refunded.

- Availability: The service should be available with an uptime commitment of 99.9% in a 30-day period; else 4 hours of extra credit will be added to the user account.

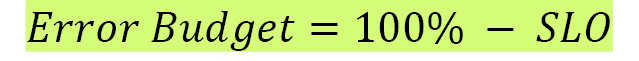

Error budgets

Google SRE defines error budgets as follows:

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

While a service needs to be reliable, it should also be mindful that if new features are not added to the service, then users might not continue to use it. A 100% reliable service will imply that the service will not have any downtime. This means that it will be increasingly difficult to add innovation via new features that could potentially attract new customers and lead to an increase in revenue. Getting to 100% reliability is expensive and complex. Instead, it's recommended to find the unique value for service reliability where customers feel that the service is reliable enough.

Unreliable systems can quickly erode users' confidence. So, it's critical to reduce the chance of system failure. SRE aims to balance the risk of unavailability with the goals of rapid innovation and efficient service operations so that users' overall happiness – with features, service, and performance – is optimized.

The error budget is basically the inverse of availability, and it tells us how unreliable our service is allowed to be. If your SLO says that 99.9% of requests should be successful in a given quarter, your error budget allows 0.1% of requests to fail. This unavailability can be generated because of bad pushes by the product teams, planned maintenance, hardware failures, and so on:

Important note

The relationship between the error budget and actual allowed downtime for a service is as follows:

If SLO = 99.5%, then error budget = 0.5% = 0.005

Allowed downtime per month = 0.005 * 30 days/month * 24 hours/day * 60 minutes/hour = 216 minutes/month

The following table represents the allowed downtime for a specific time period to achieve a certain level of availability. For downtime information calculation for a specific availability level (other than the following mentioned), refer to https://availability.sre.xyz/:

There are advantages to defining the error budget:

- Release new features while keeping an eye on system reliability.

- Roll out infrastructure updates.

- Plan for inevitable failures in networks and other similar events.

Despite planning error budgets, there are times when a system can overshoot it. In such cases, there are a few things that occur:

- Release of new features is temporarily halted.

- Increased focus on dev, system, and performance testing.

Toil

Google SRE defines toil as follows:

(Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, & Niall Murphy, Site Reliability Engineering, O'REILLY)

Here are the characteristics of toil:

- Manual: Act of manually initiating a script that automates a task.

- Repetitive: Tasks that are repeated multiple times.

- Automatable: Human executing a task instead of a machine, especially if a machine can execute with the same effectiveness.

- Tactical: Reactive tasks originating out of an interruption (such as pager alerts), rather than strategy-driven proactive tasks, are considered toil.

- No enduring value: Tasks that do not change the effective state of the service after execution.

- Linear growth: Tasks that grow linearly with an increase in traffic or service demand.

Toil is generally confused with overhead. Overhead is not the same as toil. Overhead is referred to as administrative work that is not tied to running a service, but toil refers to repetitive work that can be reduced by automation. Automation helps to lower burnout, increase team morale, increase engineering standards, improve technical skills, standardize processes, and reduce human error. Examples of tasks that represent overhead and not toil are email, commuting, expense reports, and meetings.

Canary rollouts

SRE prescribes implementing gradual change by using canary rollouts, where the concept is to introduce a change to a small portion of users to detect any imminent danger.

To elaborate, when there is a large service that needs to be sustained, it's preferable to employ a production change with unknown impact to a small portion to identify any potential issue. If any issues are found, the change can be reversed, and the impact or cost is much less than if the change was rolled out to the whole service.

The following two factors should be considered when selecting the canary population:

- The size of the canary population should be small enough that it can be quickly rolled back in case an issue arises.

- The size of the canary population should be large enough that it is a representative subset of the total population.

This concludes a high-level overview of important SRE technical practices. The next section details SRE cultural practices that are key to embrace SRE across an organization and are also critical to efficiently handle change management.

SRE's cultural practices

Defining SLIs, SLOs, and SLAs for a service, using error budgets to balance velocity (the rate at which changes are delivered to production) and reliability, identifying toil, and using automation to eliminate toil forms SRE's technical practices. In addition to these technical practices, it is important to understand and build certain cultural practices that eventually support the technical practices. Cultural practices are equally important to reduce silos within IT teams, as they can reduce the incompatible practices used by individuals within the team. The first cultural practice that will be discussed is the need for a unifying vision.

Need for a unifying vision

Every company needs a vision and a team's vision needs to align with the company's vision. The company's vision is a combination of core values, the purpose, the mission, strategies, and goals:

- Core values: Values refer to a team member's commitment to personal/organizational goals. It also reflects on how members operate within a team by building trust and psychological safety. This creates a culture where the team is open to learning and willing to take risks.

- Purpose: A team's purpose refers to the core reason that the team exists in the first place. Every team should have a purpose in the larger context of the organization.

- Mission: A team's mission refers to a well-articulated, clear, compelling, and unified goal.

- Strategy: A team's strategy refers to a plan on how the team will realize its mission.

- Goals: A team's goal gives more detailed and specific insights into what the team wants to achieve. Google recommends the use of Objectives and Key Results (OKRs), which are a popular goal-setting tool in large companies.

Once a vision statement is established for the company and the team, the next cultural practice is to ensure there is efficient collaboration and communication within the team and across cross-functional teams. This will be discussed next.

Collaboration and communication

Communication and collaboration are critical given the complexity of services and the need for these services to be globally accessible. This also means that SRE teams should be globally distributed to support services in an effective manner. Here are some SRE prescriptive guidelines:

- Service-oriented meetings: SRE teams frequently review the state of the service and identify opportunities to improve and increase awareness among stakeholders. The meetings are mandatory for team members and typically last 30-60 minutes, with a defined agenda such as discussing recent paging events, outages, any required configuration changes.

- Balanced team composition: SRE teams are spread across multiple countries and multiple time zones. This enables them to support a globally available system or service. The SRE team composition typically includes a technical lead (to provide technical guidance), a manager (who runs performance management), and a project manager, who collaborate across time zones.

- Involvement throughout the service life cycle: SRE teams are actively involved throughout the service life cycle across various stages such as architecture and design, active development, limited availability, general availability, and depreciation.

- Establish rules of engagement: SRE teams should clearly describe what channels should be used for what purpose and in what situations. This brings in a sense of clarity. SRE teams should use a common set of tools for creating and maintaining artifacts

- Encourage blameless postmortem: SRE encourages a blameless postmortem culture, where the theme is to learn from failure and the focus is on identifying the root cause of the issue rather than on individuals. A well-written postmortem report can act as an effective tool for driving positive organizational changes since the suggestions or improvements mentioned in the report can help to tune up existing processes

- Knowledge sharing: SRE teams prescribe knowledge sharing through specific means such as encouraging cross-training, creation of a volunteer teaching network, and sharing postmortems of incidents in a way that fosters collaboration and knowledge sharing.

The preceding guidelines, such as knowledge sharing along with the goal to reduce paging events or outages by creating a common set of tools, increase resistance among individuals and team members. This might also create a sense of insecurity. The next cultural practice elaborates on how to encourage psychological safety and reduce resistance to change.

Encouraging psychological safety and reducing resistance to change

SRE prescribes automation as an essential cornerstone to apply engineering principles and reduce manual work such as toil. Though eliminating toil through automation is a technical practice, there will be huge resistance to performing automation. Some may resist automation more than others. Individuals may feel as though their jobs are in jeopardy, or they may disagree that certain tasks need not be automated. SRE prescribes a cultural practice to reduce the resistance to change by building a psychologically safe environment.

In order to build a psychologically safe environment, it is first important to communicate the importance of a specific change. For example, if the change is to automate this year's job away, here are some reasons on how automation can add value:

- Provides consistency.

- Provides a platform that can be extended and applied to more systems.

- Common faults can be easily identified and resolved more quickly.

- Reduces cost by identifying problems as early in the life cycle as possible, rather than finding them in production.

Once the reason for the change is clearly communicated, here are some additional pointers that will help to build a psychologically safe environment:

- Involve team members in the change. Understand their concerns and empathize as needed.

- Encourage critics to openly express their fears as this adds a sense of freedom to team members to freely express their opinions.

- Set realistic expectations.

- Allow team members to adapt to new changes.

- Provide them with effective training opportunities and ensure that training is engaging and rewarding.

This completes an introduction to key SRE cultural practices that are critical to implementing SRE's technical practices. Subsequently, this also completes the section on SRE where we introduced SRE, discussed its evolution, and elaborated on how SRE is a prescriptive way to practically implement DevOps key pillars. The next section discusses how to implement DevOps using Google Cloud services.