In order to make our AI convincing, our agent needs to be able to respond to the events around him, the environment, the player, and even other agents. Much like real living organisms, our agent can rely on sight, sound, and other "physical" stimuli. However, we have the advantage of being able to access much more data within our game than a real organism can from their surroundings, such as the player's location, regardless of whether or not they are in the vicinity, their inventory, the location of items around the world, and any variable you chose to expose to that agent in your code:

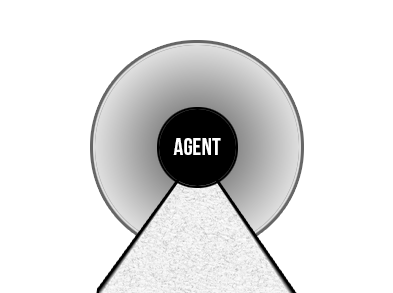

In the preceding diagram, our agent's field of vision is represented by the cone in front of it, and its hearing range is represented by the grey circle surrounding it:

Vision, sound, and other senses can be thought of, at their most essential level, as data. Vision is just light particles, sound is just vibrations, and so on. While we don't need to replicate the complexity of a constant stream of light particles bouncing around and entering our agent's eyes, we can still model the data in a way that produces believable results.

As you might imagine, we can similarly model other sensory systems, and not just the ones used for biological beings such as sight, sound, or smell, but even digital and mechanical systems that can be used by enemy robots or towers, for example sonar and radar.

If you've ever played Metal Gear Solid, then you've definitely seen these concepts in action—an enemy's field of vision is denoted on the player's mini map as cone-shaped fields of view. Enter the cone and an exclamation mark appears over the enemy's head, followed by an unmistakable chime, letting the player know that they've been spotted.