The testing methodology

Methodologies rarely consider why a penetration test is being undertaken or which data is critical to the business and needs to be protected. In the absence of this vital first step, penetration tests lose their focus.

Many penetration testers are reluctant to follow a defined methodology, fearing that it will hinder their creativity in exploiting a security weakness on the network or application. Penetration testing fails to reflect the actual activities of a malicious attacker. Frequently, the client wants to see whether you can gain administrative access to a particular system (that is, Can you root the box?). However, the attacker may be focused on copying critical data in a manner that does not require root access or cause a denial of service.

To address the limitations inherent in formal testing methodologies, they must be integrated in a framework that views the network from the perspective of an attacker, known as the cyber kill chain.

In 2009, Mike Cloppert of Lockheed Martin CERT introduced the concept that is now known as the cyber kill chain. This includes the steps taken by an adversary when they are attacking a network. It does not always proceed in a linear flow, as some steps may occur in parallel. Multiple attacks may be launched over time at the same target, and overlapping stages may occur.

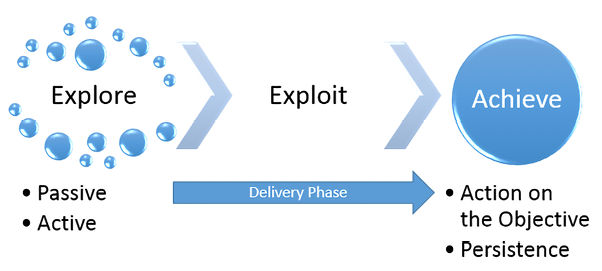

In this book, we have modified Cloppert’s cyber kill chain to more accurately reflect how attackers apply these steps when exploiting networks, applications, and data services. Figure 1.2 shows a typical cyber kill chain of an attacker:

Figure 1.2: The typical cyber kill chain an attacker may follow

A typical cyber kill chain of an attacker can be described as follows:

- Explore or reconnaissance phase: The adage, reconnaissance time is never wasted time, adopted by most military organizations, acknowledges that it is better to learn as much as possible about an enemy before engaging them. For the same reason, attackers will conduct extensive reconnaissance of a target before attacking. In fact, it is estimated that at least 70 percent of the effort of a penetration test or an attack is spent conducting reconnaissance! Generally, they will employ two types of reconnaissance:

- Passive: There is no direct interaction with the target in a hostile manner. For example, the attacker will review publicly available website(s), assess online media (especially social media sites), and attempt to determine the attack surface of the target. One particular task will be to generate a list of past and current employee names, or even an investigation into the breached databases that are publicly available.

These names will form the basis of attempts to use brute force in guessing passwords. They will also be used in social engineering attacks. This type of reconnaissance is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from the behavior of regular users.

- Active: This can be detected by the target, but it can be difficult to distinguish it from the rest of the activity that most online organizations encounter from regular traffic. Activities occurring during active reconnaissance include physical visits to target premises, port scanning, and remote vulnerability scanning.

- Passive: There is no direct interaction with the target in a hostile manner. For example, the attacker will review publicly available website(s), assess online media (especially social media sites), and attempt to determine the attack surface of the target. One particular task will be to generate a list of past and current employee names, or even an investigation into the breached databases that are publicly available.

- Delivery phase: Delivery is the selection and development of the weapon that will be used to complete the exploit during the attack. The exact weapon chosen will depend on the attacker’s intent as well as the route of delivery (for example, across the network, via a wireless connection, or through a web-based service). The impact of the delivery phase will be examined in detail in the second half of this book.

- Exploit or compromise phase: This is the point when a particular exploit is successfully applied, allowing attackers to gain a foothold in the objective system. The compromise may have occurred in a single phase (for example, a known operating system vulnerability was exploited using a buffer overflow), or it may have been a multiphase compromise (for example, if an attacker could search and download the data from the internet from sources such as https://haveibeenpwned.com or similar; these sites typically include breached data, including usernames, passwords, phone numbers, and email addresses, that will allow them to easily create a dictionary of passwords to attempt to access the Software as a Service (SaaS) applications, such as Microsoft Office 365 or Outlook Web, attempt to log in to a corporate VPN directly, or use email addresses to perform targeted email phishing techniques. The attacker could even send an SMS with malicious links to deliver a payload). Multiphase attacks are the norm when a malicious attacker targets a specific enterprise.

- Achieve phase – Action on the Objective: This is frequently, and incorrectly, referred to as the exfiltration phase because there is a focus on perceiving attacks solely as a route to steal sensitive data (such as login information, personal information, and financial information). It is in fact common for an attacker to have a different objective; for example, an attacker may wish to drop a ransomware package on their competitors to drive customers to their own business. Therefore, this phase must focus on the many possible actions of an attacker. One of the most common exploitation activities occurs when the attackers attempt to improve their access privileges to the highest possible level (vertical escalation) and to compromise as many accounts as possible (horizontal escalation).

- Achieve phase – Persistence: If there is value in compromising a network or system, then that value can likely be increased if there is persistent access. This allows attackers to maintain communications with a compromised system. From a defender’s point of view, this is the part of the cyber kill chain that is usually the easiest to detect.

Cyber kill chains are merely metamodels of an attacker’s behavior when they attempt to compromise a network or a particular data system. As a metamodel, it can incorporate any proprietary or commercial penetration testing methodology. Unlike the methodologies, however, it ensures a strategic-level focus on how an attacker approaches the network. This focus on the attacker’s activities will guide the layout and content of this book.