Using a Text Editor to Create Shell Scripts

To create your shell scripts, you’ll need a text editor that’s designed for Linux and Unix systems. You have plenty of choices, and which one you choose will depend upon several criteria:

- Are you editing on a text-mode machine or on a desktop machine?

- What features do you need?

- What is your own personal preference?

Text-mode Editors

Text-mode text editors can be used on machines that don’t have a graphical user interface installed. The two most common text-mode text editors are nano and vim. The nano editor is installed by default on pretty much every Linux distro, and is quite easy to use. To use it, just type nano, followed by the name of the file that you want to either edit or create. At the bottom of the screen, you’ll see the list of available commands. To invoke a command, press the CTRL key, followed by the letter key that corresponds to the desired command.

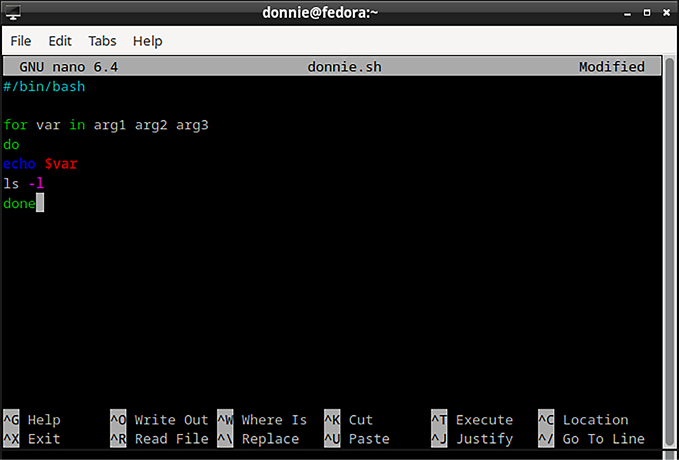

The downside of using nano is that it doesn’t have the full range of features that you might want in a programmers’ text editor. You can see here that the implementation of nano on my Fedora workstation has color-coding for the syntax, but it doesn’t automatically format the code.

Figure 1.3: The nano text editor on my Fedora workstation

Note that on other Linux distros, nano might not even have color-coding.

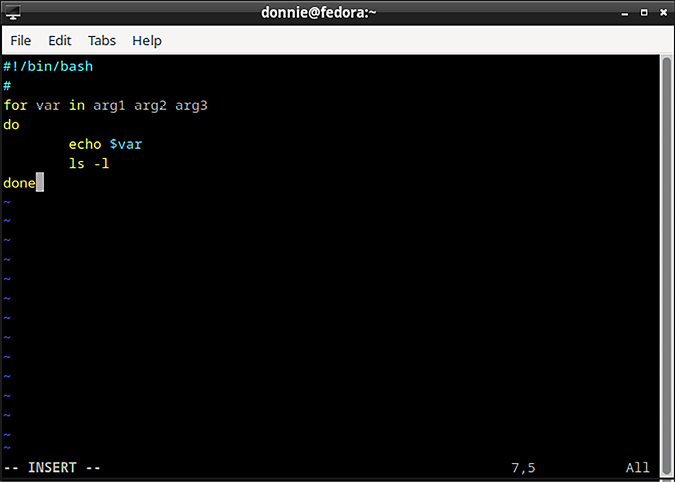

My favorite text-mode editor is vim, which has features that would make almost any programmer happy. Not only does it have color-coded syntax highlighting, but it also automatically formats your code with proper indentations, as you see here:

Figure 1.4: The vim text editor on my Fedora workstation

In reality, indentation isn’t needed for bash scripting, because bash scripts work fine without it. However, the indentation does make code easier for humans to read, and having an editor that will apply proper indentation automatically is quite handy. Additionally, vim comes with a powerful search-and-replace feature, allows you to split the screen so that you can work on two files at once, and can be customized with a fairly wide selection of plug-ins. Even though it’s a text-mode editor, you can use the right-click menu from your mouse to copy and paste text if you’re remotely logged in to your server from a desktop machine or if you’re editing a local file on your desktop machine.

The older vi text editor is normally installed on most Linux distros by default, but vim often isn’t. On some distros, the vim command will work, even if vim isn’t actually installed. That’s because the vim command on them might be pointing to either vim-minimal or even to the old vi. At any rate, to install full-fledged vim on any Red Hat-type of distro, such as RHEL, Fedora, AlmaLinux, or Rocky Linux, just do:

sudo dnf install vim-enhanced

To install vim on Debian or Ubuntu, do:

sudo apt install vim

As much as I like vim, I do have to tell you that some users are a bit put off from using it, because they believe that it’s too hard to learn. That’s because the original version of vi was created back in the Stone Age of Computing, before computer keyboards had cursor keys, backspace keys, or delete keys. The old vi commands that you used to have to use instead of these keys have been carried over to the modern implementations of vim.

So, most vim tutorials that you’ll find will still try to teach you all of those old keyboard commands.

Figure 1.5: This photo of me was taken during the Stone Age of Computing, before computer keyboards had cursor keys, backspace keys, or delete keys.

However, on the current versions of vim that you’ll install on Linux and modern Unix-like distros such as FreeBSD and OpenIndiana, the cursor keys, backspace key, and delete key all work as they do on any other text editor. So, it’s no longer necessary to learn all of those keyboard commands that you would have had to learn years ago. I mean, you’ll still need to learn a few basic keyboard commands, but not as many as you had to before.

GUI Text Editors

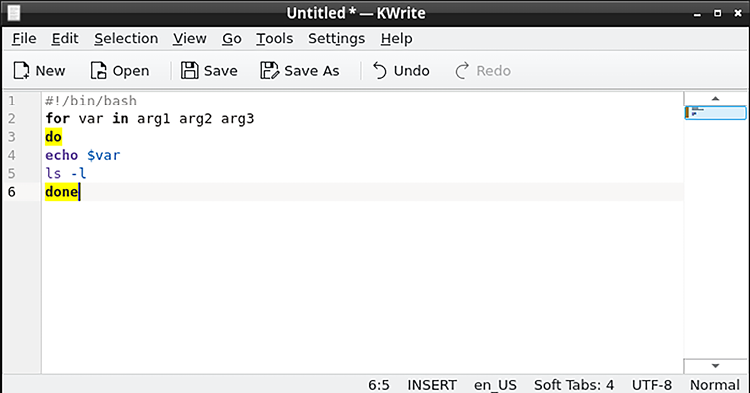

If you’re using a desktop machine, you can still use either nano or vim if you desire. But, there’s also a wide range of GUI-type editors available if you’d rather use one of them. Some sort of no-frills text editor, such as gedit or leafpad, is probably already installed on your desktop system. Some slightly fancier programmer’s editors, such as geany, kwrite, and bluefish, are available in the normal repositories of most Linux distros and some Unix-like distros. Your best bet is to play around with different editors to see what you like. Here’s an example of kwrite with color-coded syntax highlighting enabled:

Figure 1.6: The Kwrite text editor.

If you’re a Windows user, you’ll never want to create or edit a shell script on your Windows machine with a Windows text editor such as Notepad or Wordpad, and then transfer the script to your Linux machine. That’s because Windows text editors insert an invisible carriage return character at the end of each line. You can’t see them, but your Linux shell can, and will refuse to run the script. Having said that, you might at times encounter scripts that someone else created with a Windows text editor, and you’ll need to know how to fix them so that they’ll run on your Linux or Unix machine. That’s easy to do, and we’ll look at that in Chapter 7, Text Stream Filters-Part 2.

That’s about it for our overview of text editors for Linux. Let’s move on and talk about compiled versus interpreted programming languages.