Countries around the world are seeking to exert more control over content on the internet – and, by extension, their citizens. With more acts of terrorism taking place everywhere, they are now attaining a kind of online history too. With material like those from the recent Christchurch shooting proliferate as supporters upload them to any media platform they can reach. And lawmakers around the world have had enough, so this year, they hope to enact new legislation that will hold big tech companies like Facebook and Google more accountable for any terrorist-related content they host.

The Australian parliament passed legislation to crack down on violent videos on social media. Recently Sen. Elizabeth Warren, US 2020 presidential hopeful proposed to build strong anti-trust laws and break big tech companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook and Apple. And on 3rd April, Elizabeth introduced Corporate Executive Accountability Act, a new piece of legislation that would make it easier to criminally charge company executives when Americans’ personal data is breached.

Another news from Washington post states that UK has drafted an aggressive new plan to penalise Facebook, Google and other tech giants that don't stop the spread of harmful content online.

Last year, the German parliament enacted the NetzDG law, requiring large social media sites to remove posts that violate certain provisions of the German code, including broad prohibitions on “defamation of religion,” “hate speech,” and “insult.” The removal obligation is triggered not by a court order, but by complaints from users. Companies must remove the posts within 24 hours or seven days facing steep fines if they fail to do so.

Joining the bandwagon, Europe has also drafted EU Regulation on preventing the dissemination of terrorist content online. The legislation was first proposed by the EU last September as a response to the spread of ISIS propaganda online which encouraged further attacks. It covers recruiting materials such as displays of a terrorist organization’s strength, instructions for how to carry out acts of violence, and anything that glorifies the violence itself.

Social media is an important part of terrorists’ recruitment strategy, say backers of the legislation. “Whether it was the Nice attacks, whether it was the Bataclan attack in Paris, whether it’s Manchester, [...] they have all had a direct link to online extremist content,” says Lucinda Creighton, a senior adviser at the Counter Extremism Project (CEP), a campaign group that has helped shape the legislation.

The new laws require platforms to take down any terrorism-related content within an hour of a notice being issued, force them to use a filter to ensure it’s not reuploaded, and, if they fail in either of these duties, allow governments to fine companies up to 4 percent of their global annual revenue. For a company like Facebook, which earned close to $17 billion in revenue last year, that could mean fines of as much as $680 million (around €600 million).

Advocates of the legislation say it’s a set of common-sense proposals that are designed to prevent online extremist content from turning into real-world attacks. But critics, including Internet Freedom think tanks and big tech firms, claim the legislation threatens the principles of a free and open internet, and it may jeopardize the work being done by anti-terrorist groups.

The proposals are currently working their way through the committees of the European Parliament, so a lot could change before the legislation becomes law. Both sides want to find a balance between allowing freedom of expression and stopping the spread of extremist content online, but they have very different ideas about where this balance lies.

Why is the legislation needed?

Terrorists use social media to promote themselves, just like big brands do. Organizations such as ISIS use online platforms to radicalize people across the globe. Those people may then travel to join the organization’s ranks in person or commit terrorist attacks in support of ISIS in their home countries.

At its peak, ISIS has had a devastatingly effective social media strategy, which both instilled fear in its enemies and recruited new supporters. In 2019, the organization’s physical presence in the Middle East has been all but eliminated, but the legislation’s supporters argue that this means there’s an even greater need for tougher online rules. As the group’s physical power has diminished, the online war of ideas is more important than ever.

The recent attack in New Zealand where the alleged shooter identified as a 28 year old Australian man, Brenton Tarrant announced the attack on the anonymous-troll message board 8chan. He posted images of the weapons days before the attack, and made an announcement an hour before the shooting.

On 8chan, Facebook and Twitter, he also posted links to a 74-page manifesto, titled “The Great Replacement,” blaming immigration for the displacement of whites in Oceania and elsewhere. The manifesto cites “white genocide” as a motive for the attack, and calls for “a future for white children” as its goal. Further he live-streamed the attacks on Facebook, YouTube; and posted a link to the stream on 8chan.

“Every attack over the last 18 months or two years or so has got an online dimension. Either inciting or in some cases instructing, providing instruction, or glorifying,” Julian King, a British diplomat and European commissioner for the Security Union, told The Guardian when the laws were first proposed.

With the increasing frequency with which terrorists become “self-radicalized” by online material shows the importance of the proposed laws.

One-hour takedown limit; upload filters & private Terms of Service

The one-hour takedown is one of two core obligations for tech firms proposed by the legislation. Under the proposals, each EU member state will designate a so-called “competent authority.” It’s up to each member state to decide exactly how this body operates, but the legislation says they’re responsible for flagging problematic content. This includes videos and images that incite terrorism, that provide instructions for how to carry out an attack, or that otherwise promote involvement with a terrorist group.

Once content has been identified, this authority would then send out a removal order to the platform that’s hosting it, which can then delete it or disable access for any users inside the EU. Either way, action needs to be taken within one hour of a notice being issued.

It’s a tight time limit, but removing content this quickly is important to stop its spread, according to Creighton. This obligation is similar to voluntary rules that are already in place that encourage tech firms to take down content flagged by law enforcement and other trusted agencies in an hour.

Another part is the addition of a legally mandated upload filter, which would hypothetically stop the same pieces of extremist content from being continuously reuploaded after being flagged and removed — although these filters have sometimes been easy to bypass in the past.

“The frustrating thing is that [extremist content] has been flagged with the tech companies, it’s been taken down and it’s reappearing a day or two or a week later,” Creighton says, “That has to stop and that’s what this legislation targets.”

The other part is the prohibition of content using private Terms of Service (TOS), rather than national law, and to take down more material than the law actually requires. This effectively increases the power of authorities in any EU Member State to suppress information that is legal elsewhere in the EU. For example, authorities in Hungary and authorities in Sweden may disagree about a news organization sharing an interview with a current or former member of a terrorist organization that it is “promoting” or “glorifying” terrorism. Or they may differ on the legitimacy of a civil society organizations advocacy on complex issues in Chechnya, Israel, or Kurdistan. This regulation gives platforms reason to use their TOS to accommodate whichever authority wants such content taken down – and to apply that decision to users everywhere.

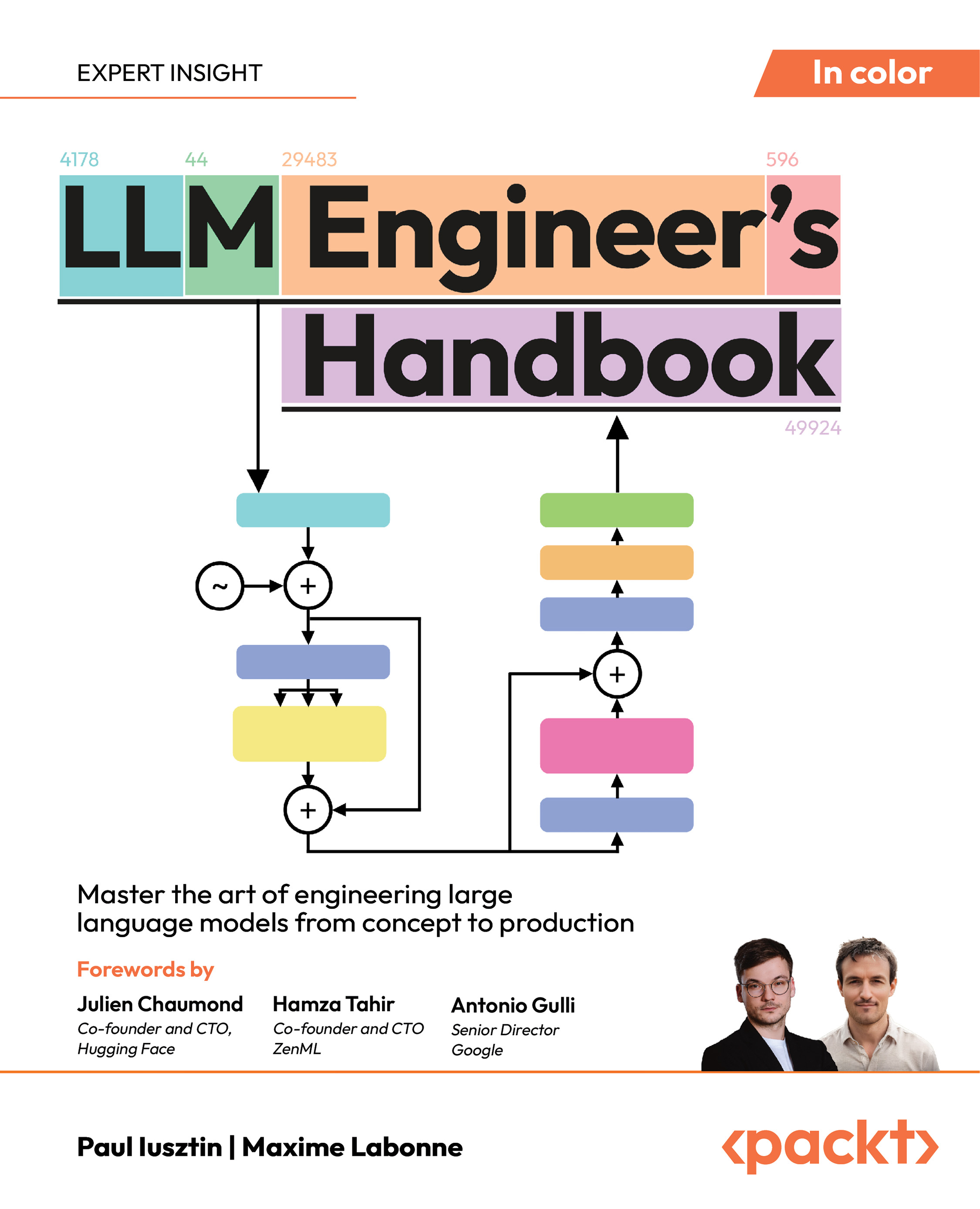

Unlock access to the largest independent learning library in Tech for FREE!

Get unlimited access to 7500+ expert-authored eBooks and video courses covering every tech area you can think of.

Renews at $19.99/month. Cancel anytime

What’s the problem with the legislation?

Critics say that the upload filter could be used by governments to censor their citizens, and that aggressively removing extremist content could prevent non-governmental organizations from being able to document events in war-torn parts of the world.

One prominent opponent is the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), a think tank funded in part by Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. Earlier this year, it published an open letter to the European Parliament, saying the legislation would “drive internet platforms to adopt untested and poorly understood technologies to restrict online expression.” The letter was co-signed by 41 campaigners and organizations, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Digital Rights Watch, and Open Rights Group.

“These filtering technologies are certainly being used by the big platforms, but we don’t think it’s right for government to force companies to install technology in this way,” the CDT’s director for European affairs, Jens-Henrik Jeppesen, told The Verge in an interview.

Removing certain content, even if a human moderator has correctly identified it as extremist in nature, could prove disastrous for the human rights groups that rely on them to document attacks. For instance, in the case of Syria’s civil war, footage of the conflict is one of the only ways to prove when human rights violations occur. But between 2012 and 2018, Google took down over 100,000 videos of attacks that were carried out in Syria’s civil war, which destroyed vital evidence of what took place. The Syrian Archive, an organization that aims to verify and preserve footage of the conflict, has been forced to backup footage on its own site to prevent the records from disappearing.

Opponents of the legislation like the CDT also say that the filters could end up acting like YouTube’s frequently criticized Content ID system. This ID allows copyright owners to file takedowns on videos that use their material, but the system will sometimes remove videos posted by their original owners, and they can misidentify original clips as being copyrighted. It can also be easily circumvented.

Opponents of the legislation also believe that the current voluntary measures are enough to stop the flow of terrorist content online. They claim the majority of terrorist content has already been removed from the major social networks, and that a user would have to go out of their way to find the content on a smaller site.

“It is disproportionate to have new legislation to see if you can sanitize the remaining 5 percent of available platforms,” Jeppesen says.

These organizations need to be able to view this content, no matter how troubling it might be, in order to investigate war crimes. Their independence from governments is what makes their work valuable, but it could also mean they’re shut out under the new legislation.

While Lucinda doesn’t believe free and public access to this information is the answer. She argues that needing to “analyze and document recruitment to ISIS in East London” isn’t a good enough excuse to leave content on the internet if the existence of that content “leads to a terrorist attack in London, or Paris or Dublin.”

The legislation is currently working its way through the European Parliament, and its exact wording could yet change. At the time of publication, the legislation’s lead committee is currently due to vote on its report on the draft regulation. After that, it must proceed through the trilogue stage — where the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, and the European Parliament debate the contents of the legislation — before it can finally be voted into law by the European Parliament.

Because the bill is so far away from being passed, neither its opponents nor its supporters believe a final vote will take place any sooner than the end of 2019. That’s because the European Parliament’s current term ends next month, and elections must take place before the next term begins in July.

Here’s the link to the proposed bill by the European Commission.

How social media enabled and amplified the Christchurch terrorist attack

Tech regulation to an extent of sentence jail: Australia’s ‘Sharing of Abhorrent Violent Material Bill’ to Warren’s ‘Corporate Executive Accountability Act’

EU’s antitrust Commission sends a “Statements of Objections” to Valve and five other video game publishers for “geo-blocking” purchases

United States

United States

Great Britain

Great Britain

India

India

Germany

Germany

France

France

Canada

Canada

Russia

Russia

Spain

Spain

Brazil

Brazil

Australia

Australia

Singapore

Singapore

Hungary

Hungary

Ukraine

Ukraine

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Estonia

Estonia

Lithuania

Lithuania

South Korea

South Korea

Turkey

Turkey

Switzerland

Switzerland

Colombia

Colombia

Taiwan

Taiwan

Chile

Chile

Norway

Norway

Ecuador

Ecuador

Indonesia

Indonesia

New Zealand

New Zealand

Cyprus

Cyprus

Denmark

Denmark

Finland

Finland

Poland

Poland

Malta

Malta

Czechia

Czechia

Austria

Austria

Sweden

Sweden

Italy

Italy

Egypt

Egypt

Belgium

Belgium

Portugal

Portugal

Slovenia

Slovenia

Ireland

Ireland

Romania

Romania

Greece

Greece

Argentina

Argentina

Netherlands

Netherlands

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Latvia

Latvia

South Africa

South Africa

Malaysia

Malaysia

Japan

Japan

Slovakia

Slovakia

Philippines

Philippines

Mexico

Mexico

Thailand

Thailand