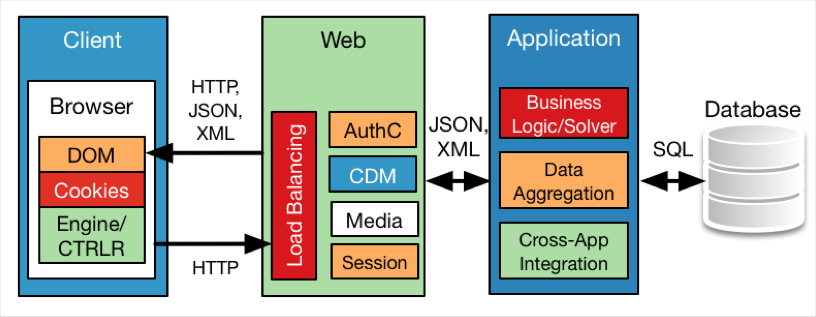

Web applications have evolved greatly over the last 15 years, emerging from their early monolithic designs to segmented approaches, which in more professionally deployed instances dominate the market now. They have also seen a shift in how these elements of architecture are hosted, from purely on-premise servers, to virtualized instances, to now pure or hybrid cloud deployments. We should also understand that the clients' role in this architecture can vary greatly. This evolution has improved scale and availability, but the additional complexity and variability involved can work against less diligent developers and operators.

The overall web application's architecture maybe physically, logically, or functionally segmented. These types of segmentation may occur in combinations; with the cross-application integration so prevalent in enterprises, it is likely that these boundaries or characteristics are always in a state of transition. This segmentation serves to improve scalability and modularity, split management domains to match the personnel or team structure, increase availability, and can also offer some much-needed segmentation to assist in the event of a compromise. The degree to which this modularity occurs and how the functions are divided logically and physically is greatly dependent on the framework that is used.

Let's discuss some of the more commonly used logical models as well as some of the standout frameworks that these models are implemented on.