What is React?

I think the one-line description of React on its home page (https://react.dev/) is concise and accurate:

”A JavaScript library for building user interfaces.”

This is perfect because, as it turns out, this is all we want most of the time. I think the best part about this description is everything that it leaves out. It’s not a mega-framework. It’s not a full-stack solution that’s going to handle everything, from the database to real-time updates over WebSocket connections. We might not actually want most of these prepackaged solutions. If React isn’t a framework, then what is it exactly?

React is just the view layer

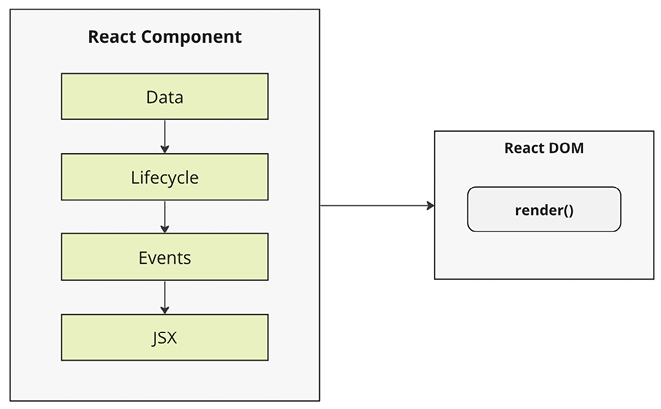

React is generally thought of as the view layer in an application. Applications are typically divided into different layers, such as the view layer, the logic layer, and the data layer. React, in this context, primarily handles the view layer, which involves rendering and updating the UI based on changes in data and application state. React components change what the user sees. The following diagram illustrates where React fits in our frontend code:

Figure 1.1: The layers of a React application

This is all there is to React – the core concept. Of course, there will be subtle variations to this theme as we make our way through the book, but the flow is more or less the same:

- Application logic: Start with some application logic that generates data.

- Rendering data to the UI: The next step is to render this data to the UI.

- React component: To accomplish this, you pass the data to a React component.

- Component’s role: The React component takes on the responsibility of getting the HTML onto the page.

You may wonder what the big deal is; React appears to be yet another rendering technology. We’ll touch on some of the key areas where React can simplify application development in the remaining sections of the chapter.

Simplicity is good

React doesn’t have many moving parts to learn about and understand. While React boasts a relatively simple API, it’s important to note that beneath the surface, React operates with a degree of complexity. Throughout this book, we will delve into these internal workings, exploring various aspects of React’s architecture and mechanisms to provide you with a comprehensive understanding. The advantage of having a small API to work with is that you can spend more time familiarizing yourself with it, experimenting with it, and so on. The opposite is true of large frameworks, where all of your time is devoted to figuring out how everything works. The following diagram gives you a rough idea of the APIs that we have to think about when programming with React:

Figure 1.2: The simplicity of the React API

React is divided into two major APIs:

- The React Component API: These are the parts of the page that are rendered by the React DOM.

- React DOM: This is the API that’s used to perform the rendering on a web page.

Within a React component, we have the following areas to think about:

- Data: This is data that comes from somewhere (the component doesn’t care where) and is rendered by the component.

- Lifecycle: For example, one phase of the lifecycle is when the component is about to be rendered. Within a React component, methods or hooks respond to the component’s entering and exiting phases of the React rendering process as they happen over time.

- Events: These are the code that we write to respond to user interactions.

- JSX: This is the syntax commonly used for describing UI structures in React components. Even though JSX is closely associated with React, it can also be used alongside other JavaScript frameworks and libraries.

Don’t fixate on what these different areas of the React API represent just yet. The takeaway here is that React, by nature, is simple. Just look at how little there is to figure out! This means that we don’t have to spend a ton of time going through API details here. Instead, once you pick up on the basics, we can spend more time on nuanced React usage patterns that fit in nicely with declarative UI structures.

Declarative UI structures

React newcomers have a hard time getting to grips with the idea that components mix in markup with their JavaScript in order to declare UI structures. If you’ve looked at React examples and had the same adverse reaction, don’t worry. Initially, we can be skeptical of this approach, and I think the reason is that we’ve been conditioned for decades by the separation of concerns principle. This principle states that different concerns, such as logic and presentation, should be separate from one another. Now, whenever we see things combined, we automatically assume that this is bad and shouldn’t happen.

The syntax used by React components is called JSX (short for JavaScript XML, also known as JavaScript Syntax Extension). A component renders content by returning some JSX. The JSX itself is usually HTML markup, mixed with custom tags for React components. The specifics don’t matter at this point; we’ll go into detail in the coming chapters.

What’s groundbreaking about the declarative JSX approach is that we don’t have to manually perform intricate operations to change the content of a component. Instead, we describe how the UI should look in different states, and React efficiently updates the actual DOM to match. As a result, React UIs become easier and more efficient to work with, resulting in better performance.

For example, think about using something such as jQuery to build your application. You have a page with some content on it, and you want to add a class to a paragraph when a button is clicked:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('#my-button').click(function() {

$('#my-paragraph').addClass('highlight');

});

});

Performing these steps is easy enough. This is called imperative programming, and it’s problematic for UI development. The problem with imperative programming in UI development is that it can lead to code that is difficult to maintain and modify. This is because imperative code is often tightly coupled, meaning that changes to one part of the code can have unintended consequences elsewhere. Additionally, imperative code can be difficult to reason about, as it can be hard to understand the flow of control and the state of an application at any given time. While this example of changing the class of an element is simple, real applications tend to involve more than three or four steps to make something happen.

React components don’t require you to execute steps in an imperative way. This is why JSX is central to React components. The XML-style syntax makes it easy to describe what the UI should look like – that is, what are the HTML elements that component is going to render?

export const App = () => {

const [isHighlighted, setIsHighlighted] = useState(false);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setIsHighlighted(true)}>Add Class</button>

<p className={isHighlighted && "highlight"}>This is paragraph</p>

</div>

);

};

In this example, we’re not just writing the imperative procedure that the browser should execute. This is more like an instruction, where we say how the UI should look and what user interaction should happen on it. This is called declarative programming and is very well suited for UI development. Once you’ve declared your UI structure, you need to specify how it changes over time.

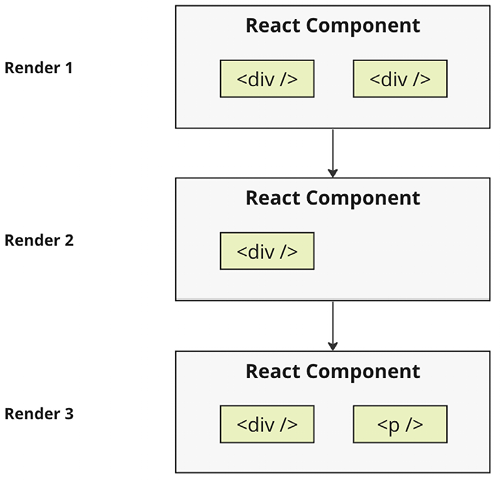

Data changes over time

Another area that’s difficult for React newcomers to grasp is the idea that JSX is like a static string, representing a chunk of rendered output. This is where data and the passage of time come into play. React components rely on data being passed into them. This data represents the dynamic parts of the UI – for example, a UI element that’s rendered based on a Boolean value could change the next time the component is rendered. Here’s a diagram illustrating the idea:

Figure 1.3: React components changing over time

Each time the React component is rendered, it’s like taking a snapshot of the JSX at that exact moment in time. As your application moves forward through time, you have an ordered collection of rendered UI components. In addition to declaratively describing what a UI should be, re-rendering the same JSX content makes things much easier for developers. The challenge is making sure that React can handle the performance demands of this approach.

Performance matters

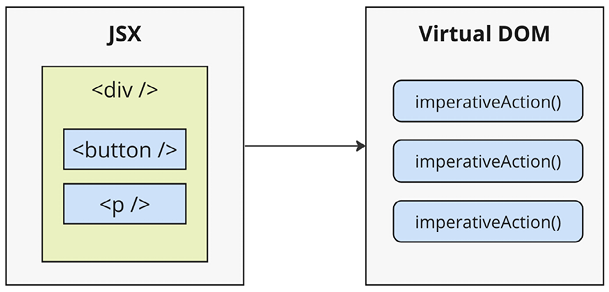

Using React to build UIs means that we can declare the structure of the UI with JSX. This is less error-prone than the imperative approach of assembling the UI piece by piece. However, the declarative approach does present a challenge with performance.

For example, having a declarative UI structure is fine for the initial rendering because there’s nothing on the page yet. So the React renderer can look at the structure declared in JSX and render it in the DOM browser.

The Document Object Model (DOM) represents HTML in the browser after it has been rendered. The DOM API is how JavaScript is able to change content on a page.

This concept is illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 1.4: How JSX syntax translates to HTML in the browser DOM

On the initial render, React components and their JSX are no different from other template libraries. For instance, there is a templating library called Handlebars used for server-side rendering, which will render a template to HTML markup as a string that is then inserted into the browser DOM. Where React is different from libraries such as Handlebars is that React can accommodate when data changes and we need to re-render the component, whereas Handlebars will just rebuild the entire HTML string, the same way it did on the initial render. Since this is problematic for performance, we often end up implementing imperative workarounds that manually update tiny bits of the DOM. We end up with a tangled mess of declarative templates and imperative code to handle the dynamic aspects of the UI.

We don’t do this in React. This is what sets React apart from other view libraries. Components are declarative for the initial render, and they stay this way even as they’re re-rendered. It’s what React does under the hood that makes re-rendering declarative UI structures possible.

In React, however, when we create a component, we describe what it should look like clearly and straightforwardly. Even as we update our components, React handles the changes smoothly behind the scenes. In other words, components are declarative for the initial render, and they stay this way even as they’re re-rendered. This is possible because React employs the virtual DOM, which is used to keep a representation of the real DOM elements in memory. It does this so that each time we re-render a component, it can compare the new content to the content that’s already displayed on the page. Based on the difference, the virtual DOM can execute the imperative steps necessary to make the changes. So not only do we get to keep our declarative code when we need to update the UI but React will also make sure that it’s done in a performant way. Here’s what this process looks like:

Figure 1.5: React transpiles JSX syntax into imperative DOM API calls

When you read about React, you’ll often see words such as diffing and patching. Diffing means comparing old content (the previous state of the UI) with new content (the updated state) to identify the differences, much like comparing two versions of a document to see what’s changed. Patching means executing the necessary DOM operations to render the new content, ensuring that only the specific changes are made, which is crucial for performance.

As with any other JavaScript library, React is constrained by the run-to-completion nature of the main thread. For example, if the React virtual DOM logic is busy diffing content and patching the real DOM, the browser can’t respond to user input such as clicks or interactions.

As you’ll see in the next section of this chapter, changes were made to the internal rendering algorithms in React to mitigate these performance pitfalls. With performance concerns addressed, we need to make sure that we’re confident that React is flexible enough to adapt to the different platforms that we might want to deploy our apps to in the future.

The right level of abstraction

Another topic I want to cover at a high level before we dive into React code is abstraction.

In the preceding section, you saw how JSX syntax translates to low-level operations that update our UI. A better way to look at how React translates our declarative UI components is via the fact that we don’t necessarily care what the render target is. The render target happens to be the browser DOM with React, but, as we will see, it isn’t restricted to the browser DOM.

React has the potential to be used for any UI we want to create, on any conceivable device. We’re only just starting to see this with React Native, but the possibilities are endless. I would not be surprised if React Toast, which is totally not a thing, suddenly becomes relevant, where React targets toasters that can singe the rendered output of JSX onto bread. React’s abstraction level strikes a balance that allows for versatility and adaptability while maintaining a practical and efficient approach to UI development.

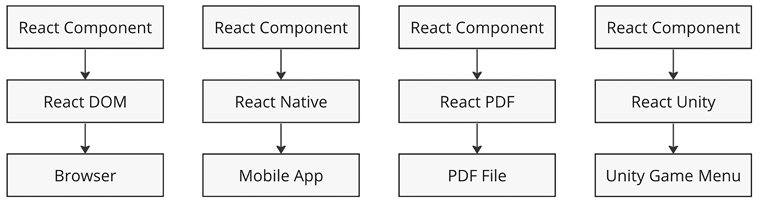

The following diagram gives you an idea of how React can target more than just the browser:

Figure 1.6: React abstracts the target rendering environment from the components that we implement

From left to right, we have React DOM, React Native, React PDF, and React Unity. All of these React Renderer libraries accept the React component and return a platform-specific result. As you can see, to target something new, the same pattern applies:

- Implement components specific to the target.

- Implement a React renderer that can perform the platform-specific operations under the hood.

This is, obviously, an oversimplification of what’s actually implemented for any given React environment. But the details aren’t so important to us. What’s important is that we can use our React knowledge to focus on describing the structure of our UI on any platform.

Now that you understand the role of abstractions in React, let’s see what’s new in React.