Our first jQuery-powered web page

Now that we have covered the range of features available to us with jQuery, we can examine how to put the library into action. To get started, we need a copy of jQuery.

Downloading jQuery

No installation is required. To use jQuery, we just need a publicly available copy of the file, whether that copy is on an external site or our own. As JavaScript is an interpreted language, there is no compilation or build phase to worry about. Whenever we need a page to have jQuery available, we will simply refer to the file's location from a <script> element in the HTML document.

The official jQuery website (http://jquery.com/) always has the most up-to-date, stable version of the library, which can be downloaded right from the home page of the site. Several versions of jQuery may be available at any given moment; the most appropriate for us as site developers will be the latest uncompressed version of the library. This can be replaced with a compressed version in production environments.

As jQuery's popularity has grown, companies have made the file freely available through their Content Delivery Networks (CDNs). Most notably, Google (http://code.google.com/apis/ajaxlibs/documentation/), and Microsoft (http://www.asp.net/ajax/cdn) offer the file on powerful, low-latency servers distributed around the world for fast download regardless of the user's location. While a CDN-hosted copy of jQuery has speed advantages due to server distribution and caching, using a local copy can be convenient during development. Throughout this book we'll use a copy of the file stored on our own system, which will allow us to run our code whether we're connected to the Internet or not.

Setting up jQuery in an HTML document

There are three pieces to most examples of jQuery usage: the HTML document, CSS files to style it, and JavaScript files to act on it. For our first example, we'll use a page with a book excerpt that has a number of classes applied to portions of it. This page includes a reference to the latest version of the jQuery library, which we have downloaded, renamed jquery.js, and placed in our local project directory, as follows:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Through the Looking-Glass</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="01.css">

<script src="jquery.js"></script>

<script src="01.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Through the Looking-Glass</h1>

<div class="author">by Lewis Carroll</div>

<div class="chapter" id="chapter-1">

<h2 class="chapter-title">1. Looking-Glass House</h2>

<p>There was a book lying near Alice on the table,and while she sat watching the White King (for shewas still a little anxious about him, and had theink all ready to throw over him, in case he faintedagain), she turned over the leaves, to find somepart that she could read,

<span class="spoken">

"—for it's all in some language I don't know,"

</span>

she said to herself.

</p>

<p>It was like this.</p>

<div class="poem">

<h3 class="poem-title">YKCOWREBBAJ</h3>

<div class="poem-stanza">

<div>sevot yhtils eht dna ,gillirb sawT'</div>

<div>;ebaw eht ni elbmig dna eryg diD</div>

<div>,sevogorob eht erew ysmim llA</div>

<div>.ebargtuo shtar emom eht dnA</div>

</div>

</div>

<p>She puzzled over this for some time, but at lasta bright thought struck her.

<span class="spoken">

"Why, it's a Looking-glass book, of course! And ifI hold it up to a glass, the words will all go theright way again."

</span>

</p>

<p>This was the poem that Alice read.</p>

<div class="poem">

<h3 class="poem-title">JABBERWOCKY</h3>

<div class="poem-stanza">

<div>'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves</div>

<div>Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;</div>

<div>All mimsy were the borogoves,</div>

<div>And the mome raths outgrabe.</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>Tip

File Paths

The actual layout of files on the server does not matter. References from one file to another just need to be adjusted to match the organization we choose. In most examples in this book, we will use relative paths to reference files (../images/foo.png) rather than absolute paths (/images/foo.png). This will allow the code to run locally without the need for a web server.

Immediately following the normal HTML preamble, the stylesheet is loaded. For this example, we'll use the following:

body {

background-color: #fff;

color: #000;

font-family: Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

}

h1, h2, h3 {

margin-bottom: .2em;

}

.poem {

margin: 0 2em;

}

.highlight {

background-color: #ccc;

border: 1px solid #888;

font-style: italic;

margin: 0.5em 0;

padding: 0.5em;

}After the stylesheet is referenced, the JavaScript files are included. It is important that the script tag for the jQuery library be placed before the tag for our custom scripts; otherwise, the jQuery framework will not be available when our code attempts to reference it.

Note

Throughout the rest of this book, only the relevant portions of HTML and CSS files will be printed. The files in their entirety are available at the book's companion website http://book.learningjquery.com.

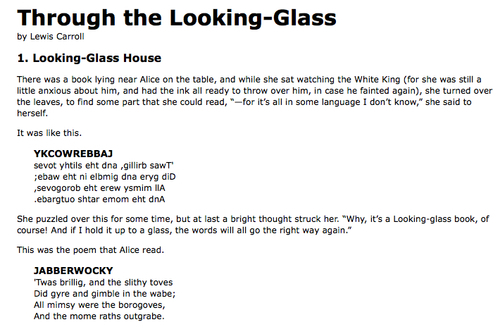

Now we have a page that looks similar to the following screenshot:

We will use jQuery to apply a new style to the poem text.

Note

This example is to demonstrate a simple use of jQuery. In real-world situations, this type of styling could be performed purely with CSS.

Adding our jQuery code

Our custom code will go in the second, currently empty, JavaScript file which we included from the HTML using <script src="01.js"></script>. For this example, we only need three lines of code, as follows:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('div.poem-stanza').addClass('highlight');

});Finding the poem text

The fundamental operation in jQuery is selecting a part of the document. This is done with the $() function. Typically, it takes a string as a parameter, which can contain any CSS selector expression. In this case, we wish to find all of the <div> elements in the document that have the poem-stanza class applied to them, so the selector is very simple. However, we will cover much more sophisticated options through the course of the book. We will step through many ways of locating parts of a document in Chapter 2, Selecting Elements.

When called, the $() function returns a new jQuery object instance

, which is the basic building block we will be working with from now on. This object encapsulates zero or more DOM elements, and allows us to interact with them in many different ways. In this case, we wish to modify the appearance of these parts of the page, and we will accomplish this by changing the classes applied to the poem text.

Injecting the new class

The .addClass() method, like most jQuery methods, is named self-descriptively; it applies a CSS class to the part of the page that we have selected. Its only parameter is the name of the class to add. This method, and its counterpart, .removeClass()

, will allow us to easily observe jQuery in action as we explore the different selector expressions available to us. For now, our example simply adds the highlight class, which our stylesheet has defined as italicized text with a gray background and a border.

Note that no iteration is necessary to add the class to all the poem stanzas. As we discussed, jQuery uses implicit iteration

within methods such as .addClass(), so a single function call is all it takes to alter all of the selected parts of the document.

Executing the code

Taken together, $() and .addClass() are enough for us to accomplish our goal of changing the appearance of the poem text. However, if this line of code is inserted alone in the document header, it will have no effect. JavaScript code is generally run as soon as it is encountered in the browser, and at the time the header is being processed, no HTML is yet present to style. We need to delay the execution of the code until after the DOM is available for our use.

With the $(document).ready() construct, jQuery allows us to schedule function calls for firing once the DOM is loaded—without necessarily waiting for images to fully render. While this event scheduling is possible without the aid of jQuery, $(document).ready() provides an especially elegant cross-browser solution that:

Uses the browser's native DOM ready implementations when available and adds a

window.onloadevent handler as a safety netAllows for multiple calls to

$(document).ready()and executes them in the order in which they are calledExecutes functions passed to

$(document).ready()even if they are added after the browser event has already occurredHandles the event scheduling asynchronously to allow scripts to delay it if necessary

Simulates a DOM ready event in some older browsers by repeatedly checking for the existence of a DOM method that typically becomes available at the same time as the DOM

The .ready() method's parameter can accept a reference to an already defined function, as shown in the following code snippet:

function addHighlightClass() {

$('div.poem-stanza').addClass('highlight');

}

$(document).ready(addHighlightClass);Listing 1.1

However, as demonstrated in the original version of the script, and repeated in Listing 1.2, as follows, the method can also accept an anonymous function (sometimes also called a lambda function ), as follows:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('div.poem-stanza').addClass('highlight');

});Listing 1.2

This anonymous function idiom is convenient in jQuery code for methods that take a function as an argument when that function isn't reusable. Moreover, the closure it creates can be an advanced and powerful tool. However, it may also have unintended consequences and ramifications on memory use, if not dealt with carefully. The topic of closures is discussed fully in Appendix A, JavaScript Closures.

The finished product

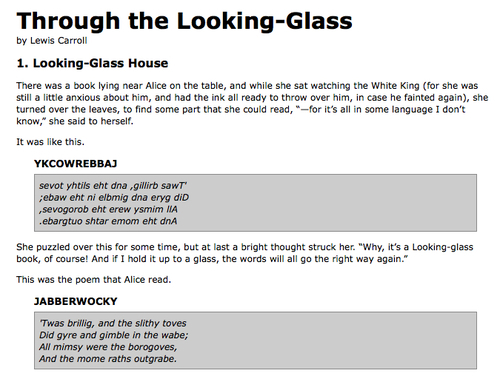

Now that our JavaScript is in place, the page looks similar to the following screenshot:

The poem stanzas are now italicized and enclosed in boxes, as specified by the 01.css stylesheet, due to the insertion of the highlight class by the JavaScript code.