Understanding methods

On their own, variables can't do much more than keep track of their assigned values. While this is vital, they are not very useful on their own in terms of creating meaningful applications. So, how do we go about creating actions and driving behavior in our code? The short answer is by using methods.

Before we get to what methods are and how to use them, we should clarify a small point of terminology. In the world of programming, you'll commonly see the terms method and function used interchangeably, especially in regards to Unity.

Since C# is an object-oriented language (this is something that we'll cover in Chapter 5, Working with Classes, Structs, and OOP), we'll be using the term method for the rest of the book to conform to standard C# guidelines.

When you come across the word function in the Scripting Reference or any other documentation, think method.

Methods drive actions

Similarly to variables, defining programming methods can be tediously long-winded or dangerously brief; here's another three-pronged approach to consider:

- Conceptually, methods are how work gets done in an application.

- Technically, a method is a block of code containing executable statements that run when the method is called by name. Methods can take in arguments (also called parameters), which can be used inside the method's scope.

- Practically, a method is a container for a set of instructions that run every time it's executed. These containers can also take in variables as inputs, which can only be referenced inside the method itself.

Taken all together, methods are the bones of any program—they connect everything and almost everything is built off of their structure.

You can find an in-depth guide to methods in the Microsoft C# documentation at https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/programming-guide/classes-and-structs/methods.

Methods are placeholders too

Let's take an oversimplified example of adding two numbers together to drive the concept home. When writing a script, you're essentially laying down lines of code for the computer to execute in sequential order. The first time you need to add two numbers together, you could just add them like in the following code block:

SomeNumber + AnotherNumber

But then you conclude that these numbers need to be added together somewhere else.

Instead of copying and pasting the same line of code, which results in sloppy or "spaghetti" code and should be avoided at all costs, you can create a named method that will take care of this action:

AddNumbers()

{

SomeNumber + AnotherNumber

}

Now AddNumbers is holding a place in memory, just like a variable; however, instead of a value, it holds a block of instructions. Using the name of the method (or calling it) anywhere in a script puts the stored instructions at your fingertips without having to repeat any code.

If you find yourself writing the same lines of code over and over, you're likely missing a chance to simplify or condense repeated actions into common methods.

This produces what programmers jokingly call spaghetti code because it can get messy. You'll also hear programmers refer to a solution called the Don't Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle, which is a mantra you should keep in mind.

As before, once we've seen a new concept in pseudocode, it's best if we implement it ourselves, which is what we'll do in the next section to drive it home.

Let's open up LearningCurve again and see how a method works in C#. Just like with the variables example, you'll want to copy the code into your script exactly as it appears in the following screenshot. I've deleted the previous example code to make things neater, but you can, of course, keep it in your script for reference:

- Open up

LearningCurvein Visual Studio. - Add a new variable to line 8:

public int AddedAge = 1; - Add a new method to line 16 that adds

CurrentAgeandAddedAgetogether and prints out the result:void ComputeAge() { Debug.Log(CurrentAge + AddedAge); } - Call the new method inside

Startwith the following line:ComputeAge();Double-check that your code looks like the following screenshot before you run the script in Unity:

Figure 2.6: LearningCurve with new ComputeAge method

- Save the file, and then go back and hit play in Unity to see the new Console output.

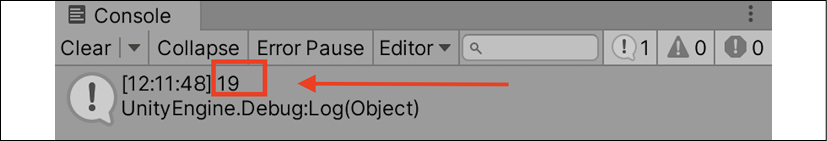

You defined your first method on lines 16 to 19 and called it on line 13. Now, wherever ComputeAge() is called, the two variables will be added together and printed to the console, even if their values change. Remember, you set CurrentAge to 18 in the Unity Inspector, and the Inspector value will always override the value in a C# script:

Figure 2.7: Console output from changing the variable value in the Inspector

Go ahead and try out different variable values in the Inspector panel to see this in action! More details on the actual code syntax of what you just wrote are coming up in the next chapter.

With a bird's-eye view of methods under our belts, we're ready to tackle the biggest topic in the programming landscape—classes!