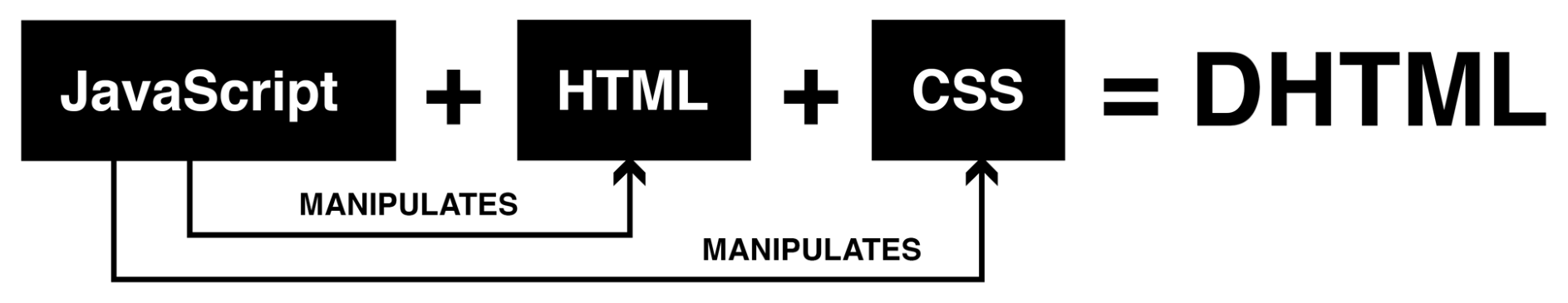

JavaScript was created by Brendan Eich in 1995, with the goal of being a glue language. It was intended to help web designers and amateurs easily manipulate and derive behavior from their HTML. JavaScript was able to do this via the DOM API, a set of interfaces provided by the browser that would give access to the parsed representation of HTML. Soon after this, DHTML became the popular term, referring to the more dynamic user interfaces that JavaScript enabled: everything from animated rollover button states to client-side form validation. Eventually came the rise of Ajax, which enabled communication between the client and the server. This opened up a considerable fountain of potential applications. The web, previously purely the domain of documents, was now on the way to becoming a powerhouse of processor- and memory-intensive applications:

In 1995, nobody could have predicted that JavaScript would one day be used to build complex web applications, program robots, query databases, write plugins for photo manipulation software, and be behind one of the most popular server runtimes in existence, Node.js.

In 1997, not long after its creation, JavaScript was standardized by Ecma International under the name ECMAScript, and it is still undergoing frequent changes under the TC39 committee. Most recent versions of the language have been named according to the year of their release, such as ECMAScript 2020 (ES2020).

Due to its burgeoning capabilities, JavaScript has attracted a passionate community that drives its growth and ubiquity. And due to its considerable popularity, there are now countless different ways to do the same thing in JavaScript. There are thousands of popular frameworks, libraries, and utilities. The language too is changing on a near-constant basis in reaction to the increasing demands of its applications. This creates a great challenge: among all of this change, while being pushed and pulled in different directions, how can we know how to write the best possible code? Which frameworks should we use? What conventions should we employ? How should we test our code? How should we craft sensible abstractions?

To answer these questions, we need to briefly go back to basics. And that is the purpose of this chapter. We'll be discussing the following:

- What the true purpose of the code is

- Who our users are and what problems they have

- What it means to write code for humans