Configuring administrator access with sudo

By now, we’ve already used sudo quite a few times in this book. At this point, you should already be aware of the fact that sudo allows you to execute commands as if you were logged in as another user, with root being the default. However, we haven’t had any formal discussion about it yet, nor have we discussed how to actually modify which of your user accounts are able to utilize sudo.

On all Linux systems, you should protect your root account with a strong password and limit it to being used by as few people as possible. On Ubuntu, the root account is locked anyway, so unless you unlocked it by setting a password (or you’re using a version of Ubuntu supplied by a VPS provider), it cannot be used to log in to the system. Using sudo is an alternative to logging in as root to execute commands directly, so you can give your administrators access to perform tasks that require root privileges with sudo without actually giving them your root password or unlocking the root account. In fact, sudo allows you to be a bit more granular. Using root directly is basically all or nothing—if someone knows the root password and the root account is enabled, that person is not limited and can do whatever they want. With sudo, that can also be true, but you can actually restrict some users to use only particular commands and therefore limit the scope of what they are able to do on the system. For example, you could give an admin access to install software updates but not allow them to reboot the server.

By default, members of the sudo group are able to use sudo without any restrictions. Basically, members of this group can do anything root can do (which is everything). During installation, the user account you created was made a member of sudo. To give additional users access to sudo, all you would need to do is add them to the sudo group:

sudo usermod -aG sudo <username>

Not all distributions utilize the sudo group by default, or even automatically install sudo. Other distributions require you to install sudo manually and may use another group (such as wheel) to govern access to sudo.

But again, that gives those users access to everything, and that may or may not be what you want. To actually configure sudo, we use the visudo command. This command assists you with editing /etc/sudoers, which is the configuration file that governs sudo access. Although you can edit /etc/sudoers yourself with a text editor, configuring sudo in that way is strongly discouraged. The visudo command checks to make sure your changes follow the correct syntax and helps prevent you from accidentally destroying the file. This is a very good approach, because if you did make any errors in the /etc/sudoers file, you may wind up in a situation where no one is able to gain administrative control over the server. And while there are ways to recover from such a mistake, it’s certainly not a very pleasant situation to find yourself in! So, the takeaway here is never to edit the /etc/sudoers file directly; always use visudo to do so.

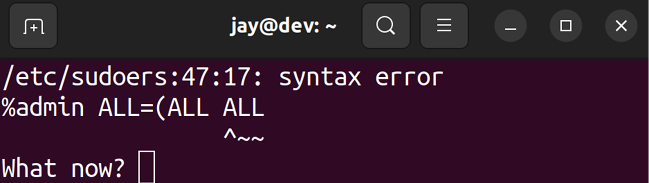

Here’s an example of the type of warning the visudo command shows when you make a mistake:

Figure 2.13: The visudo command showing an error

If you do see this error, press e to return to edit the file, and then correct the mistake.

The way this works is when you run visudo from your shell, you are brought into a text editor with the /etc/sudoers file opened up. You can then make changes to the file and save it like you would any other text file. By default, Ubuntu opens up the nano text editor when you use visudo. With nano, you can save changes using Ctrl + w, and you can exit the text editor with Ctrl + x.

So visudo allows you to make changes to who is able to access sudo. But how do you actually make these changes? Go ahead and scroll through the /etc/sudoers file that visudo opens and you should see a line similar to the following:

%sudo ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

This is the line of configuration that enables sudo access to anyone who is a member of the sudo group. You can change the group name to any that you’d like, for example, perhaps you’d like to create a group called admins instead. If you do change this, make sure that you actually create that group and add yourself and your staff to be members of it before you edit the /etc/sudoers file or log off; it would be rather embarrassing if you found yourself locked out of administrator access to the server.

Of course, you don’t have to enable access by group. You can actually call out a username instead. With the /etc/sudoers file, groups are preceded by %, while users are not. As an example of this, we also have the following line in the file:

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Here, we’re calling out a username (in this case, root), but the rest of the line is the same as the one I pointed out before. While you can certainly copy this line and paste it one or more times (substituting root for a different username) to grant access to others, using the group approach is really the best way. It’s easier to add and remove users from a group (such as the sudo group) than it is to use visudo each time.

So, at this point, you’re probably wondering what the options on /etc/sudoers configuration lines actually mean. So far, both examples used ALL=(ALL:ALL) All. In order to fully understand sudo, understanding the other fields is extremely important, so let’s go through them (using the root line again as an example).

The first ALL means that root is able to use sudo from any terminal. The second ALL means that root can use sudo to impersonate any other user. The third ALL means that root can impersonate any other group. Finally, the last ALL refers to what commands this user is able to use; in this case, any command they wish.

To help drive this home, I’ll give some additional examples. Here’s a hypothetical example:

charlie ALL=(ALL:ALL) /sbin/reboot,/sbin/shutdown

Here, we’re allowing user charlie to execute the reboot and shutdown commands. If user charlie tries to do something else (such as install a package), they will receive an error message:

Sorry, user charlie is not allowed to execute '/usr/bin/apt install tmux' as root on ubuntu.

However, if charlie wants to use the reboot or shutdown commands on the server, they will be able to do so because we explicitly called out those commands while setting up this user’s sudo access. We can limit this further by changing the first ALL to a machine name, in this case, ubuntu, to reference the host name of the server I’m using for my examples. I’ve also changed the command that charlie is allowed to run:

charlie ubuntu=(ALL:ALL) /usr/bin/apt

It’s always a good idea to use full paths to commands when editing sudo permissions, rather than the shortened versions. For example, we used /usr/bin/apt here, instead of just apt. This is important, as the user could create a script named apt to do mischievous things that we normally wouldn’t allow them to do. By using the full path, we’re limiting the user to the binary stored at that path.

Now, charlie is only able to use apt. They can use apt update, apt dist-upgrade, and any other sub-command of apt. But if they try to reboot the server, remove protected files, add users, or anything else we haven’t explicitly set, they will be prevented from doing so.

We have another problem, though. We’re allowing charlie to impersonate other users. This may not be completely terrible given the context of installing packages (impersonating another user would be useless unless that user also has access to install packages), but it’s bad form to allow this unless we really need to. In this case, we could just remove the (ALL:ALL) from the line altogether to prevent charlie from using the -u option of sudo to run commands as other users:

charlie ubuntu= /usr/bin/apt

On the other hand, if we actually do want charlie to be able to impersonate other users (but only specific users), we can call out the username and group that charlie is allowed to act on behalf of by setting those values:

charlie ubuntu=(dscully:admins) ALL

In that example, charlie is able to run commands on behalf of the user dscully and the group admins.

Of course, there is much more to sudo than what I’ve mentioned in this section. Entire books could be written about sudo (and have been), but 99% of what you will need for your daily management of this tool involves how to add access to users while being specific about what each user is able to do. As a best practice, use groups when you can (for example, you could have an apt group, a reboot group, and so on) and be as specific as you can regarding who is able to do what. This way, you’re not only able to keep the root account private (or even better, disabled), but you also have more accountability on your servers.

Now that we’ve explored granting access to sudo, we will next take a look at permissions, which give us even more control over what our users are able to access.