They hide the use cases

As developers, we like to create new code that implements shiny new use cases. But we usually spend much more time changing existing code than we do creating new code. This is not only true for those dreaded legacy projects in which we’re working on a decades-old code base but also for a hot new greenfield project after the initial use cases have been implemented.

Since we’re so often searching for the right place to add or change functionality, our architecture should help us to quickly navigate the code base. How does a layered architecture hold up in this regard?

As already discussed previously, in a layered architecture, it easily happens that domain logic is scattered throughout the layers. It may exist in the web layer if we’re skipping the domain logic for an “easy” use case. And it may exist in the persistence layer if we have pushed a certain component down so it can be accessed from both the domain and persistence layers. This already makes finding the right spot to add new functionality hard.

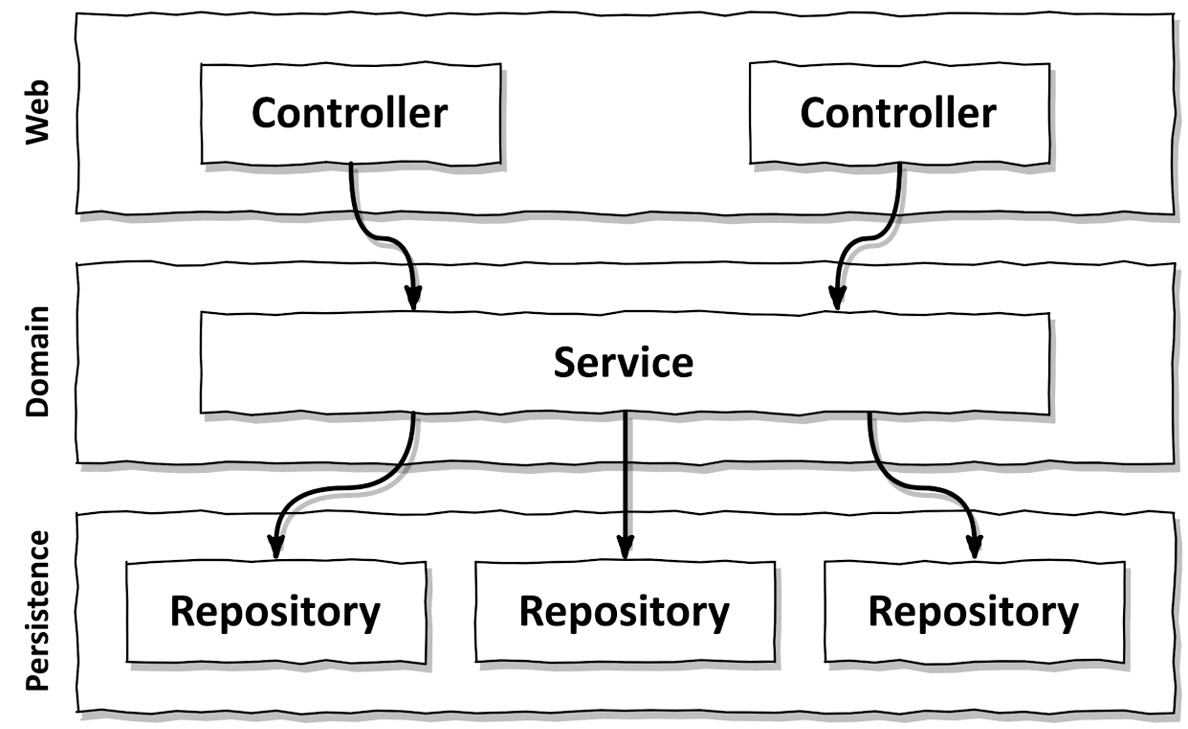

But there’s more. A layered architecture does not impose rules on the “width” of domain services. Over time, this often leads to very broad services that serve multiple use cases (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 – “Broad” services make it hard to find a certain use case within the code base

A broad service has many dependencies on the persistence layer and many components in the web layer depend on it. This not only makes the service hard to test but also makes it hard for us to find the code responsible for the use case we want to work on.

How much easier would it be if we had highly specialized, narrow domain services that each serve a single use case? Instead of searching for the user registration use case in UserService, we would just open up RegisterUserService and start hacking away.