Introducing Blazor

Blazor is an open-source web UI framework. That’s a lot of buzzwords in the same sentence, but simply put, it means that you can create interactive web applications using HTML, CSS, and C# with full support for bindings, events, forms and validation, dependency injection, debugging, and much more, with Blazor. We will explore these in this book.

In 2017, Steve Sanderson (well-known for creating the Knockout JavaScript framework and who works for the ASP.NET team at Microsoft) was about to do a session called Web Apps can’t really do *that*, can they? at the developer conference NDC Oslo.

But Steve wanted to show a cool demo, so he thought, Would it be possible to run C# in WebAssembly? He found an old inactive project on GitHub called Dot Net Anywhere, which was written in C and used tools (similar to what we just did) to compile the C code into WebAssembly.

He got a simple console app running in the browser. This would have been a fantastic demo for most people, but Steve wanted to take it further. He thought, Is it possible to create a simple web framework on top of this?, and went on to see if he could also get the tooling working.

When it was time for his session, he had a working sample to create a new project, create a to-do list with great tooling support, and run the project in the browser.

Damian Edwards (the .NET team) and David Fowler (the .NET team) were also at the NDC conference. Steve showed them what he was about to demo, and they described the event as their heads exploded and their jaws dropped.

And that’s how the prototype of Blazor came into existence.

The name Blazor comes from a combination of Browser and Razor (which is the technology used to combine code and HTML). Adding an L made the name sound better, but other than that, it has no real meaning or acronym.

There are a few different flavors of Blazor, including Blazor Server, Blazor WebAssembly, Blazor Hybrid (using .NET MAUI), and Server-Side Rendering.

The different versions have some pros and cons, all of which I will cover in the upcoming sections and chapters.

Blazor Server

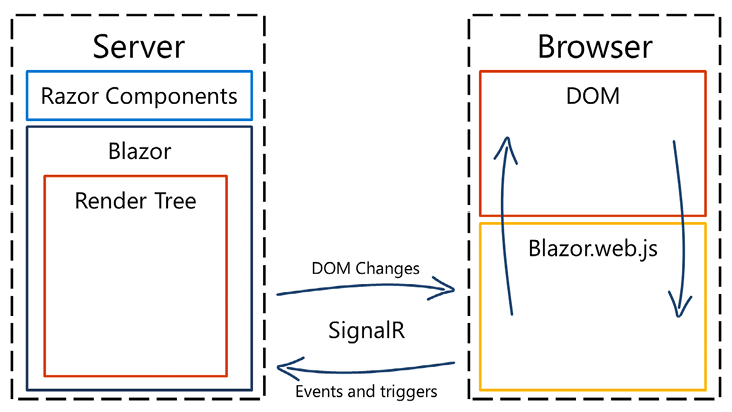

Blazor Server uses SignalR to communicate between the client and the server, as shown in the following diagram:

Figure 1.1: Overview of Blazor Server

SignalR is an open-source, real-time communication library that will create a connection between the client and the server. SignalR can use many different means of transporting data and automatically selects the best transport protocol based on your server and client capabilities. SignalR will always try to use WebSockets, which is a transport protocol built into HTML5. If WebSockets is not enabled, it will gracefully fall back to another protocol.

Blazor is built with reusable UI elements called components (more on components in Chapter 4, Understanding Basic Blazor Components). Each component contains C# code and markup. A component can include other components. You can use Razor syntax to mix markup and C# code or do everything in C# if you wish. The components can be updated by user interaction (pressing a button) or triggers (such as a timer).

The components are rendered into a render tree, a binary representation of the DOM containing object states and any properties or values. The render tree will keep track of any changes compared to the previous render tree, and then send only the things that changed over SignalR using a binary format to update the DOM.

JavaScript will receive the changes on the client side and update the page accordingly. If we compare this to traditional ASP.NET, we only render the component itself, not the entire page, and we only send over the actual changes to the DOM, not the whole page.

There are advantages to Blazor Server:

- It contains just enough code to establish that the connection is downloaded to the client, so the site has a small footprint, which makes the site startup really fast.

- Since everything is rendered on the server, Blazor Server is more SEO-friendly.

- Since we are running on the server, the app can fully utilize the server’s capabilities.

- The site will work on older web browsers that don’t support WebAssembly.

- The code runs on the server and stays on the server; there is no way to decompile the code.

- Since the code is executed on your server (or in the cloud), you can make direct calls to services and databases within your organization.

There are, of course, some disadvantages to Blazor Server as well:

- You need to always be connected to the server since the rendering is done on the server. If you have a bad internet connection, the site might not work. The big difference compared to a non-Blazor Server site is that a non-Blazor Server site can deliver a page and then disconnect until it requests another page. With Blazor, that connection (SignalR) must always be connected (minor disconnections are okay).

- There is no offline/PWA (Progressive Web App) mode since it needs to be connected.

- Every click or page update must do a round trip to the server, which might result in higher latency. It is important to remember that Blazor Server will only send the changed data. I have not experienced any slow response times personally.

- Since we have to have a connection to the server, the load on that server increases and makes scaling difficult. To solve this problem, you can use the Azure SignalR hub to handle the constant connections and let your server concentrate on delivering content.

- Each connection stores the information in the server’s memory, increasing memory use and making load balancing more difficult.

- To be able to run Blazor Server, you have to host it on an ASP.NET Core-enabled server.

At my workplace, we already had a large site, so we decided to use Blazor Server for our projects. We had a customer portal and an internal CRM tool, and our approach was to take one component at a time and convert it into a Blazor component.

We quickly realized that, in most cases, it was faster to remake the component in Blazor rather than continue to use ASP.NET MVC and add functionality. The User Experience (UX) for the end-user became even better as we converted.

The pages loaded faster. We could reload parts of the page as we needed instead of the whole page, and so on.

We found that Blazor introduced a new problem: the pages became too fast. Our users didn’t understand whether data had been saved because nothing happened; things did happen, but too fast for the users to notice. Suddenly, we had to think more about UX and how to inform the user that something had changed. This is, of course, a very positive side effect of Blazor.

Blazor Server is not the only way to run Blazor – you can also run it on the client (in the web browser) using WebAssembly.

Blazor WebAssembly

There is another option: instead of running Blazor on a server, you can run it inside your web browser using WebAssembly.

The Mono runtime is a tool that lets you run programs made with C# and other .NET languages on various operating systems, not just Windows.

Microsoft has taken the Mono runtime (which is written in C) and compiled that into WebAssembly.

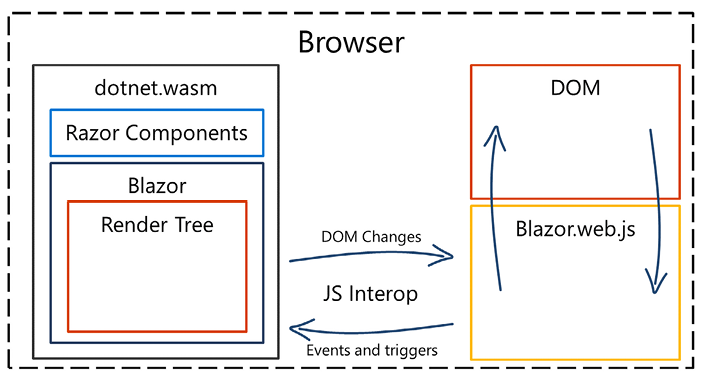

The WebAssembly version of Blazor works very similarly to the server version, as shown in the following diagram. We have moved everything off the server, and it is now running within our web browser:

Figure 1.2: Overview of Blazor WebAssembly

A render tree is still created, and instead of running the Razor pages on the server, they are now running inside our web browser. Instead of SignalR, since WebAssembly doesn’t have direct DOM access, Blazor updates the DOM with direct JavaScript interop.

The Mono runtime that’s compiled into WebAssembly is called dotnet.wasm. The page contains a small piece of JavaScript that will make sure to load dotnet.wasm. Then, it will download blazor.boot.json, a JSON file containing all the files the application needs to run, as well as the application’s entry point.

If we look at the default sample site that is created when we start a new Blazor project in Visual Studio, the Blazor.boot.json file contains 63 dependencies that need to be downloaded. All the dependencies get downloaded and the app boots up.

As we mentioned previously, dotnet.wasm is the mono runtime that’s compiled into WebAssembly. It runs .NET DLLs – the ones you have written and the ones from .NET Framework (which is needed to run your app) – in your browser.

When I first heard of this, I got a bit of a bad taste. It’s running the whole .NET runtime in my browser?! But then, after a while, I realized how amazing that is. You can run any .NET Standard DLLs in your web browser.

In the next chapter, we will look at exactly what happens and in what order code gets executed when a WebAssembly app boots up.

There are, of course, some advantages of Blazor WebAssembly:

- Since the code runs in the browser, creating a PWA is easy.

- It does not require a connection to the server. Blazor WebAssembly will work offline.

- Since we’re not running anything on the server, we can use any backend server or file share (no need for a .NET-compatible server in the backend).

- No round trips mean that you can update the screen faster (that is why there are game engines that use WebAssembly).

There are some disadvantages to Blazor WebAssembly as well:

- Even if we compare it to other large sites, the footprint of Blazor WebAssembly is large and there are a large number of files to download.

- To access any on-site resources, you will need to create a Web API to access them. You cannot access the database directly.

- The code runs in the browser, meaning it can be decompiled. All app developers are used to this, but it is perhaps not as common for web developers.

I wanted to put WebAssembly to the test! When I was seven years old, I got my first computer, a Sinclair ZX Spectrum. I remember that I sat down and wrote the following:

10 PRINT "Jimmy"

20 GOTO 10

That was my code; I made the computer write my name on the screen over and over!

That was when I decided that I wanted to become a developer to make computers do stuff.

After becoming a developer, I wanted to revisit my childhood and decided I wanted to build a ZX Spectrum emulator. In many ways, the emulator has become my test project instead of a simple Hello World when I encounter new technology. I’ve had it running on a Gadgeteer, Xbox One, and even a HoloLens (to name a few platforms/devices).

But is it possible to run my emulator in Blazor?

It took me only a couple of hours to get the emulator working with Blazor WebAssembly by leveraging my already built .NET Standard DLL; I only had to write the code specific to this implementation, such as the keyboard and graphics. This is one of the reasons Blazor (both Server and WebAssembly) is so powerful: it can run libraries that have already been made. Not only can you leverage your knowledge of C#, but you can also take advantage of the large ecosystem and .NET community.

You can find the emulator here: http://zxbox.com. This is one of my favorite projects to work on, as I keep finding ways to optimize and improve the emulator.

Building interactive web applications used to only be possible with JavaScript. Now, we know we can use Blazor WebAssembly and Blazor Server, but which one of these new options is the best?

Blazor WebAssembly versus Blazor Server

Which one should we choose? The answer is, as always, it depends. You have seen the advantages and disadvantages of both.

If you have a current site that you want to port over to Blazor, I recommend going for the server side; once you have ported it, you can make a new decision as to whether you want to go for WebAssembly as well. This way, it is easy to port parts of the site, and the debugging experience is better with Blazor Server.

Suppose your site runs on a mobile browser or another unreliable internet connection. In that case, you might consider going for an offline-capable (PWA) scenario with Blazor WebAssembly since Blazor Server needs a constant connection.

The startup time for WebAssembly is a bit slow, but there are ways to combine the two hosting models to have the best of both worlds. We will cover this in Chapter 16, Going Deeper into WebAssembly.

There is no silver bullet when it comes to this question, but read up on the advantages and disadvantages and see how they affect your project and use cases.

With .NET 8, we have more opportunities to mix and match the different technologies, so the question becomes less relevant since we can choose to have one specific component running Blazor Server and another running Blazor WebAssembly (more on that later in this chapter).

We can run Blazor server-side and on the client, but what about desktop and mobile apps?

Blazor Hybrid/.NET MAUI

.NET MAUI is a cross-platform application framework. The name comes from .NET Multi-platform App UI and is the next version of Xamarin. We can use traditional XAML code to create our cross-platform application just as with Xamarin. However, .NET MAUI also targets desktop operating systems that will enable running our Blazor app on Windows and even macOS.

.NET MAUI has its own template that enables us to run Blazor inside of a .NET MAUI application using a Blazor WebView. This is called Blazor Hybrid. Blazor Hybrid works in a similar way to the other hosting models (Blazor Server and Blazor WebAssembly). It has a render tree and updates the Blazor WebView, which is a browser component in .NET MAUI. This is a bit oversimplified perhaps but we have a whole chapter on Blazor Hybrid (Chapter 18, Visiting .NET MAUI). Using Blazor Hybrid, we also get access to native APIs (not only Web APIs), making it possible to take our application to another level.

We will take a look at .NET MAUI in Chapter 18, Visiting .NET MAUI.

Sometimes we don’t need interactive components, we just need to render some content and be done. In .NET 8, we have a new way of doing that.

Server-Side Rendering (SSR)

Server-side rendering is the new kid on the Blazor block. It makes it possible to use the Razor syntax to build web pages that are rendered server-side just like MVC or Razor Pages. This is called Static Server-side Rendering. It has some additional features that will keep scrolling in the previous position even though the whole page is reloaded, which is called enhanced form navigation. This will only render static pages, with no interactivity (with a few exceptions). There is also something called streaming rendering that will load the page even faster. This mode is called streaming server-side rendering. During long-running tasks, streaming rendering will first send the HTML it has and then update the DOM once the long-running task is complete, giving it a more interactive feeling.

But sometimes we want interactivity, and choosing between Blazor Server or Blazor WebAssembly can be a bit hard. But what if I told you we don’t have to choose anymore? We can mix it up.

The feature formerly known as Blazor United

This next feature was called “Blazor United” when Microsoft first spoke of it but is now simply part of Blazor, not an extra feature. I still want to mention the name because the community still uses it, and chances are you might have heard it and are wondering why I am not mentioning it.

It is a really cool feature: we can pick and choose what components will run using SSR and what components will use Blazor Server, Blazor WebAssembly, or (hope you are sitting down for this) a mix of the two. Previously, we had to choose one of the two (Blazor Server or Blazor WebAssembly), but now we can combine the technologies to get the best of both worlds. We can now tell each component how we want it to render and we can mix and match throughout the site. The new “auto” feature means the first time our users visit the site, they will run Blazor Server. This is to get a quick connection and get data to the user as quickly as possible. In the background, the WebAssembly version is downloaded and cached so the next time they visit the site, it will use the cached Blazor WebAssembly version. If the WebAssembly version can be downloaded and started within 100 milliseconds, it will load only the WebAssembly version. If it takes longer, it will start up Blazor Server and download in the background. This is one of the ways we can speed up the download speed of our Blazor site. We can combine all of these technologies, pre-render the content on the server using Static Server-side Rendering, make the site interactive using Blazor Server (using SignalR), and then switch over to Blazor WebAssembly without the “long” download time.