In tkinter, the typical one-line textbox widget is called Entry. In this recipe, we will add such an Entry widget to our GUI. We will make our label more useful by describing what the Entry widget is doing for the user.

Text box widgets

Getting ready

This recipe builds upon the Creating buttons and changing their text property recipe.

How to do it...

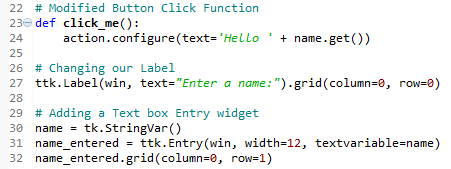

Check out the following code:

GUI_textbox_widget.py

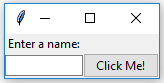

Now, our GUI looks like this:

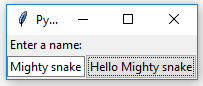

After entering some text and clicking the button, there is the following change in the GUI:

How it works...

In line 24, we get the value of the Entry widget. We have not used OOP yet, so how come we can access the value of a variable that was not even declared yet?

Without using OOP classes, in Python procedural coding, we have to physically place a name above a statement that tries to use that name. So how come this works (it does)?

The answer is that the button click event is a callback function, and by the time the button is clicked by a user, the variables referenced in this function are known and do exist.

Life is good.

Line 27 gives our label a more meaningful name; for now, it describes the text box below it. We moved the button down next to the label to visually associate the two. We are still using the grid layout manager, which will be explained in more detail in Chapter 2, Layout Management.

Line 30 creates a variable, name. This variable is bound to the Entry widget and, in our click_me() function, we are able to retrieve the value of the Entry widget by calling get() on this variable. This works like a charm.

Now we see that while the button displays the entire text we entered (and more), the textbox Entry widget did not expand. The reason for this is that we hardcoded it to a width of 12 in line 31.

- Python is a dynamically typed language and infers the type from the assignment. What this means is that if we assign a string to the name variable, it will be of the string type, and if we assign an integer to name, its type will be integer.

- Using tkinter, we have to declare the name variable as the type tk.StringVar() before we can use it successfully. The reason is that tkinter is not Python. We can use it from Python, but it is not the same language.