Common operations (or, how to exit Vim)

We will now focus on interacting with Vim without the use of a mouse or navigational menus. Here’s a meme I found some years back:

Figure 1.25 – An accurate portrayal of a typical Vim user (source: https://twitter.com/iamdevloper/status/435555976687923200)

Programming is a focus-intensive task on its own. Hunting through context menus is nobody’s idea of a good time, and keeping our hands on the home row of your keyboard helps trim constant switching between a keyboard and a mouse.

In this section, we’ll learn how to open (and, more importantly, close) Vim, save files, and make basic edits.

Opening files

First, start your favorite Command Prompt (Terminal in Linux and macOS, Cygwin in Windows). We’ll be working on a very basic Python application. For simplicity’s sake, let’s make a simple square root calculator. Run the following command:

$ vim spam.py

GUI for the win!

If you’re using gVim, you can open a file by going into a File menu and choosing Open. Sometimes, a graphical interface is exactly what you need!

This opens a file named spam.py. If the file existed, you’d see its contents here, but since it doesn’t, we’re greeted by an empty screen, as shown in the following example:

![Figure 1.26 – Opening a new file in Vim as indicated by the [New File] text](https://static.packt-cdn.com/products/9781835081877/graphics/image/B21349_01_26.jpg)

Figure 1.26 – Opening a new file in Vim as indicated by the [New File] text

You can tell that the file doesn’t exist by the [New File] text next to a file name at the bottom of the screen. Woohoo! You’ve just opened your first file with Vim!

If you already have Vim open, you can load a file by typing the following, and hitting Enter:

:e spam.py

You have just executed your first Vim command! Pressing the colon character (:) enters a command-line mode, which lets you enter a line of text that Vim will interpret as a command. Commands are terminated by hitting the Enter key, which allows you to perform various complex operations, as well as accessing your system’s Command line. The :e command stands for edit.

Vim help often refers to the Enter key as a <CR>, which stands for carriage return.

Changing text

By default, you’re in Vim’s normal mode, meaning that every key press corresponds to a particular command. Hit i on your keyboard to enter an insert mode. This will display -- INSERT -- in a status line (at the bottom), and, if you’re using gVim, it will change the cursor from a block to a vertical line, as can be seen in the following example:

Figure 1.27 – Vim in insert mode, as indicated by -- INSERT -- in the bottom-left corner

The insert mode behaves just like any other modeless editor. Normally, we wouldn’t spend a lot of time in insert mode except for adding new text.

Modes, modes, modes

You’ve already encountered three of Vim’s modes: command-line mode, normal mode, and insert mode. This book will cover more modes – see Chapter 3 for details and explanation.

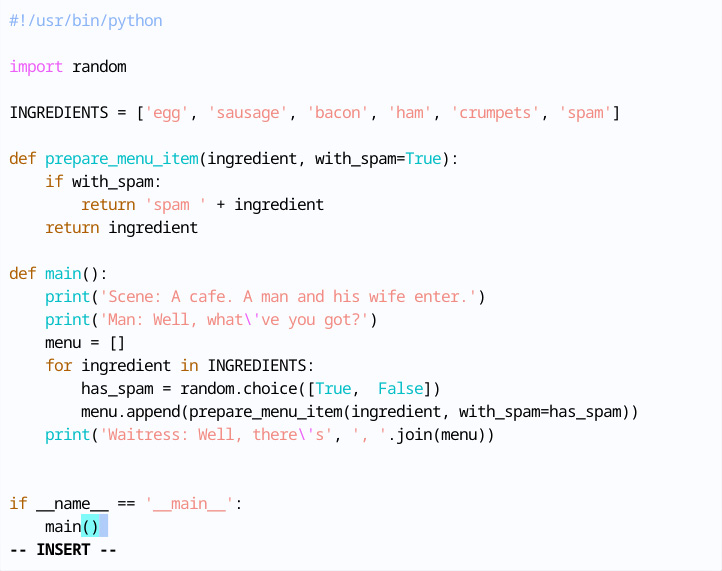

Let’s create our Python application by typing in the following code. We’ll be navigating this little snippet throughout this chapter:

Figure 1.28 – A simple Python 3 program referencing Monty Python’s “Spam” sketch

To get back to normal mode in Vim, hit Esc on your keyboard. You’ll see that -- INSERT -- has disappeared from the status line. Now, Vim is ready to take commands from you again!

This code isn’t very good

The preceding code does not display Python best practices and is provided to illustrate some of Vim’s capabilities.

Saving and closing files

Let’s save our file! Execute the following command:

:w

Don’t forget to execute the command!

Don’t forget to hit Enter at the end of a command to execute it.

:w stands for write.

Naming files

The write command can also be followed by a filename, making it possible to write to a different file, other than the one that is open (:w spam_2.py). To change the currently open file to a new one when saving, use the :saveas command: :saveas spam_2.py.

Let’s exit Vim and check whether the file was indeed created. :q stands for quit. You can also combine write and quit commands to write and exit by executing :wq.

:q

If you made changes to a file and want to exit Vim without saving the changes, you’ll have to use :q! to force Vim to quit. The exclamation mark at the end of the command forces its execution.

Shortening commands

Many commands in Vim have shorter and longer versions. For instance, :e, :w, and :q are short versions of :edit, :write, and :quit. In the Vim manual, the optional part of the command is often annotated in square brackets ([]); for example, :w[rite] or :e[dit].

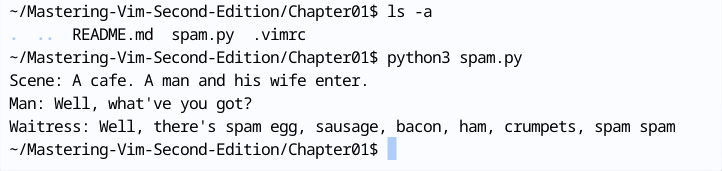

Now that we’re back in our system’s command line, let’s check the contents of a current directory, as seen in the following code:

$ ls $ python3 spam.py

The following screenshot shows what the two preceding commands should output:

Figure 1.29 – Output of the ls -a and python3 spam.py commands

Command spotlight

In Unix, ls lists the contents of a current directory (the –a flag shows hidden files). python3 spam.py executes the script using a Python 3 interpreter.

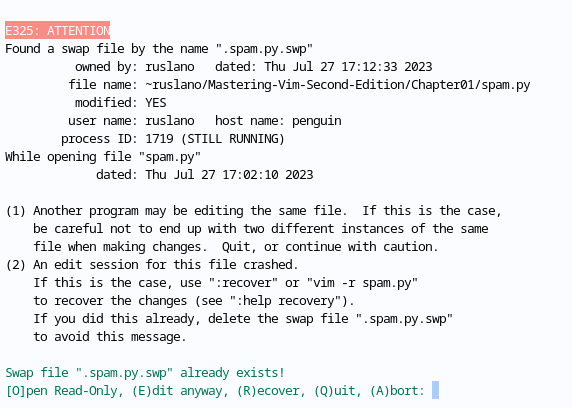

A word about swap files

By default, Vim keeps track of the changes you make to files in swap files. The swap files are created as you edit the files, and are used to recover the contents of your files in case either Vim, your SSH session, or your machine crashes. If you don’t exit Vim cleanly, or try to edit the same file multiple times at the same time, you’ll be greeted by the following screen:

Figure 1.30 – A swap file error when attempting to open a file

You can either hit r to recover the swap file contents or d to delete the swap file and dismiss the changes. If you decide to recover the swap file, you can prevent the same message from showing up the next time you open the file in Vim by reopening a file, running :e, and pressing d to delete the swap file (although Vim won’t let you delete the swap file if the file in question is currently open in another Vim instance).

By default, Vim creates files such as <filename>.swp and .<filename>.swp in the same directory as the original file. If you don’t like your file system being littered with swap files, you can change this behavior by telling Vim to place all the swap files in a single directory. To do so, add the following to your .vimrc:

set directory=$HOME/.vim/swap//

Note that double directory delimiter at the end; this setting won’t work correctly without it!

For Windows users

If you’re on Windows, you should use set directory=%USERDATA%\.vim\swap// (note the direction of the last two slashes).

You can also choose to disable the swap files completely by adding set noswapfile to your .vimrc.

“But,” I hear you say, “I spend most of my time navigating code (or text) rather than writing it top to bottom!” Never fret, as this is what sets Vim apart from conventional editors. The next section will teach you to navigate around what you just wrote.