Chapter 7. Functions

In the previous chapter, we learned about packaging a set of commands in a script. In this chapter, we will look at using functions to provide the same kind of containment. We will discuss the differences between functions and scripts, and drill down more into parameters. The specific topics covered in this chapter include the following:

- Defining functions

- Comparing scripts and functions

- Executing functions

- Comment-based help

- Function output

- Parameters

- Default values

Another kind of container

Scripts are a simple way to reuse your commands. Scripts are file-based, so there is an inherent limitation—you can only have one script per file. This may not seem like a problem, but when you have hundreds or even thousands of pieces of code, you may want to be able to group them together and not have so many files on the disk.

Comparing scripts and functions

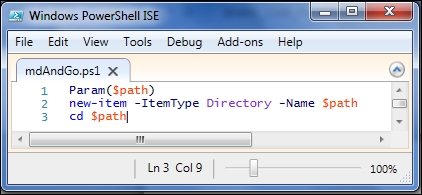

The primary difference between a function and a script is that a script is a file, whereas a function is contained within a file. Consider the MdAndGo.ps1 script from Chapter 6, Scripts:

As a function, this could be written like this:

You can see from this example that the functions are defined using the function keyword. Comparing these two examples, you can also see that the body of the function (the scriptblock after the function name) is identical to the contents of the script. Practically speaking, anything you can do in a script, you can do in a function also. If this is true (it is true), why would we want to use functions?

The first reason is simple convenience. If I write a dozen bits of code pertaining to a particular subject area, I would want these bits of code to be in one place. If I use scripts, I can put all of these in the same folder, and this gives a bit of coherence. On the other hand, if I use functions, I can put all of these functions in the same file. Since they're all in the same file, I can edit the file all at once and make the changes to the functions more easily. Seeing the functions in the same file can help to understand the relationships between the code, and into repeated code or possibilities for refactoring.

Second, functions are exposed in PowerShell via a PSDrive called Function:. I can see all of the functions that have been loaded into my current session using cmdlets such as Get-ChildItem, or its commonly used alias dir:

Tip

PSProviders and PSDrives

PowerShell uses PSProviders and PSDrives to provide access to hierarchical data sources using the same cmdlets that you would use to access filesystems. The Function: drive, mentioned here, holds all the functions loaded into the current session. Other PSDrives include the registry drives (HKLM: and HCKU:), the Variable: drive, the ENV: drive of environment variables, and the Cert: drive that provides access to the certificate store.

Executing and calling functions

As seen in figure in the Comparing scripts and functions section, defining a function involves using the function keyword and surrounding the code you want with a scriptblock. Executing this function statement simply adds the function definition to the current PowerShell session. To subsequently call the function, you use the function name like you would a cmdlet name, and supply parameters and arguments just like you would for a cmdlet or script.

Tip

Storing the MdAndGo function in a file called MdAndGo.ps1 can be confusing because we're using the same name for the two things. You dot-source the ps1 file to load the function into the session, then you can execute this function. Dot-sourcing the file doesn't run the function. If we had written this as a script, on the other hand, we could have executed the logic of the script without dot-sourcing.

Tip

Warning!

A common mistake of new PowerShell users is to call a function using parentheses to surround the parameters and commas to separate them. When you do this, PowerShell thinks you are creating an array and passes the array as an argument to the first parameter.

Naming conventions

Looking at the list of functions in the Function: drive, you will see some odd ones, such as CD.., CD\, and A:. These are created to help the command-line experience and are not typical functions. The names of these functions, though, show an interesting difference between functions and scripts, since it should be clear that you can't have a file named A:.ps1. Function naming, in general, should follow the same naming convention as cmdlets, namely Verb-Noun, where the verb is from the verb list returned by Get-Verb and the noun is a singular noun that consistently identifies what kinds of things are being referred to. Our MdAndGo function, for example, should have been named according to this standard. One reasonable name would be Set-NewFolderLocation.

Comment-based help

Simply defining a function creates a very basic help entry. Here's the default help for the MdAndGo function that we wrote earlier in the chapter:

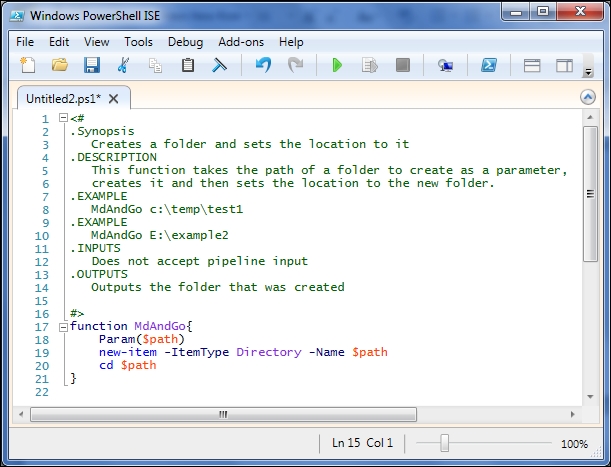

We haven't given PowerShell enough to build a useful help entry, but fortunately for us there is a simple way to include help content through comments. This feature in PowerShell is called comment-based help and is documented thoroughly in the about_comment_based_help help topic. For our purposes, we will add enough information to show that we're able to affect the help output, but we won't go into much detail.

With comment-based help, you will include a specially formatted comment immediately before the function. Keywords in the comment indicate where the help system should get the text for different areas in the help topic. Here's what our function looks like with an appropriate comment:

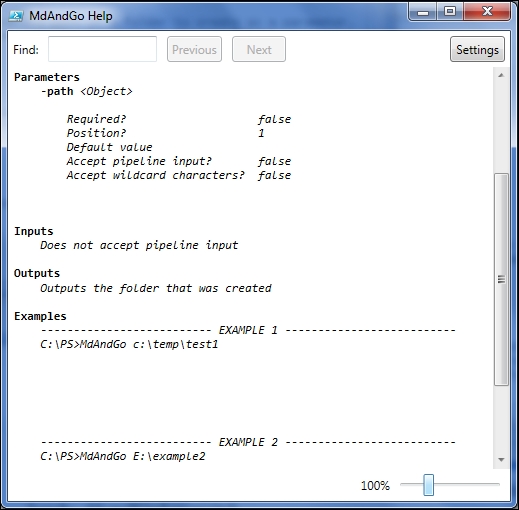

After executing the file to create the function, we can test the comment-based help using get-help MdAndGo, just as before:

Since we included examples, we can either use the –Examples switch or use the really handy –ShowWindow switch:

Note that we didn't need to number our examples or include the C:\PS> prompt. These are added automatically by the help system.

Parameters revisited

Just like scripts, functions can take parameters. Remember that parameters are placeholders, which let you vary the execution of the function (or script) based on the value that is passed to the parameter (called the argument). The MdAndGo function that we wrote earlier had a single parameter, but you can use as many parameters as you want. For instance, if you had a process that copied items from one folder to another and you wanted to write a function to make sure that both the source and destination folders already exist, you could write a function like this:

It should be clear from this example that parameters in the Param() statement are separated by commas. Remember that you don't use commas to separate the arguments you pass when you call the function. Also, the Param() statement needs to be the first statement in the function.

Typed parameters

Something else you might have noticed in this example is that we have specified that both the parameters have to be strings. It's hard to test this, since anything in the command-line is already a string. Let's write a function to output the average of two integers:

Tip

Here, we've used [int] to specify that the $a and $b parameters are integers. Specifying a type allows us to make certain assumptions about the values in these variables, namely, that they are numeric and it makes sense to average them. Other common types used in PowerShell are [String] and [DateTime].

The function works if you pass numeric arguments, but passing strings (such as orange and apple) causes an error. If you read the error message, you can see that PowerShell tried to figure out how to change "orange" into a number, but couldn't come up with a transformation that works. PowerShell has a very versatile parameter binding mechanism that attempts a number of methods to transform the arguments you pass into the type of parameters you have specified.

Switches

Besides using types like string and int, you can also use the switch type, which indicates a parameter that is either present or absent. We've seen switch parameters in cmdlets, such as the –Recurse switch parameter for Get-ChildItem. Remember that you don't specify an argument to a switch parameter. You either supply the parameter (such as –Recurse) or you don't. Switch parameters allow for easy on/off or true/false input. The parameter can be tested easily in an if statement like this:

Typed parameters

Something else you might have noticed in this example is that we have specified that both the parameters have to be strings. It's hard to test this, since anything in the command-line is already a string. Let's write a function to output the average of two integers:

Tip

Here, we've used [int] to specify that the $a and $b parameters are integers. Specifying a type allows us to make certain assumptions about the values in these variables, namely, that they are numeric and it makes sense to average them. Other common types used in PowerShell are [String] and [DateTime].

The function works if you pass numeric arguments, but passing strings (such as orange and apple) causes an error. If you read the error message, you can see that PowerShell tried to figure out how to change "orange" into a number, but couldn't come up with a transformation that works. PowerShell has a very versatile parameter binding mechanism that attempts a number of methods to transform the arguments you pass into the type of parameters you have specified.

Switches

Besides using types like string and int, you can also use the switch type, which indicates a parameter that is either present or absent. We've seen switch parameters in cmdlets, such as the –Recurse switch parameter for Get-ChildItem. Remember that you don't specify an argument to a switch parameter. You either supply the parameter (such as –Recurse) or you don't. Switch parameters allow for easy on/off or true/false input. The parameter can be tested easily in an if statement like this:

Switches

Besides using types like string and int, you can also use the switch type, which indicates a parameter that is either present or absent. We've seen switch parameters in cmdlets, such as the –Recurse switch parameter for Get-ChildItem. Remember that you don't specify an argument to a switch parameter. You either supply the parameter (such as –Recurse) or you don't. Switch parameters allow for easy on/off or true/false input. The parameter can be tested easily in an if statement like this:

Default values for parameters

You can also supply default values for parameters in the Param() statement. If no argument is given for a parameter that has a default, the default value is used for this parameter. Here's a simple example:

Using parameters is a powerful technique to make your functions applicable to more situations. This kind of flexibility is the key to write reusable functions.

Output

The functions that I've shown so far in this chapter have either explicitly used the return keyword, or used write-host to output text to the console instead of returning the data. However, the mechanism that PowerShell uses for function output is much more complex for several reasons.

The first complication is that the return keyword is completely optional. Consider the following four functions:

We can see that they all output the same value (100) by adding them all together:

The reason that these functions do the same thing is that PowerShell uses the concept of streams to deal with data coming out of a function. Data that we consider "output" uses the output stream. Any value that isn't used somehow is written to the output stream, as is a value given in a return statement. A value can be used in many ways. Some common ways of using a value are:

- Assigning the value to a variable

- Using the value as a parameter to a function, script, or cmdlet

- Using the value in an expression

- Casting the value to

[void]or piping it toOut-NullTip

[void]is a special type that indicates that there is no actual value. Casting a value to[void]is essentially throwing away the value.

The last function, Test-Output4, shows that we can explicitly write to the output stream using write-output.

Another interesting feature of the output stream is that the values are placed in the output stream immediately, rather than waiting for the function to finish before outputting everything. If you consider running DIR C:\ -recurse, you can imagine that you would probably want to see the output before the whole process is complete, so this makes sense.

Functions are not limited to a single output value, either. As I stated earlier, any value that isn't used is output from the function. Thus, the following functions output two values and four values, respectively:

The output from these strange functions illustrates another property of PowerShell functions, namely, they can output more than one kind of object.

In practice, your functions will generally output one kind of object, but if you're not careful, you might accidentally forget to use a value somewhere and that value will become part of the output. This is a source of great confusion to PowerShell beginners, and can even cause people who have been using PowerShell to scratch their heads from time to time. The key is to be careful, and if in doubt, use Get-Member to see what kind of objects you get out of your function.

Summary

The functions in PowerShell are powerful and extremely useful to create flexible, reusable code. Parameters, including switch parameters, allow you to tailor the execution of a function to meet your needs. PowerShell functions behave differently from functions in many other languages, potentially outputting multiple objects of different types and at different times.

In the next chapter, we will look at PowerShell modules, a feature added in PowerShell 2.0 to help gather functions and scripts into libraries.

For further reading

Get-Help about_FunctionsGet-Help about_ParametersGet-Help about_ReturnGet-Help about_Comment_Based_HelpGet-Help about_ProvidersGet-Help about_Core_Commands