Functions

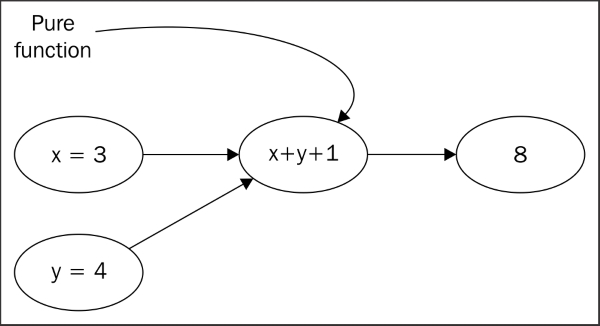

Functional programming includes a lot about functions. There are different kinds of functions in programming, for example, pure functions. A pure function depends only on its input to compute the output. Let's try the following example to make use of functions:

scala> val addThem = (x: Int, y: Int) => x + y + 1 addThem: (Int, Int) => Int = <function2> scala> addThem(3,4) res2: Int = 8

As long as the function lives, it will always give the result 8 given the input (3,4).Take a look at the following example of a pure function:

Figure 1.1: Pure functions

The functions worked on the input and produced the output, without changing any state. What does the phrase "did not change any state" mean? Here is an example of a not-so-pure function:

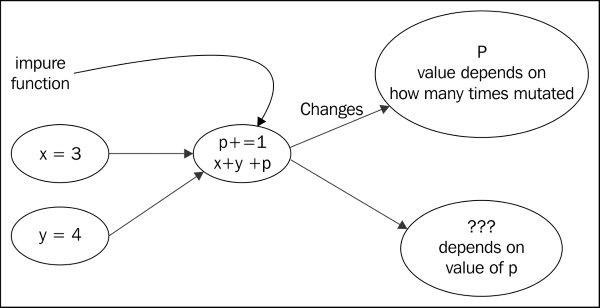

scala> var p = 1 p: Int = 1 scala> val addP = (x: Int, y: Int) => { | p += 1 | x + y + p | } addP: (Int, Int) => Int = <function2> scala> addP(3, 4) res4: Int = 9 scala> addP(3, 4) res5: Int = 10

This addP function changes the world—this means that it affects its surroundings. In this case, the variable p. Here is the diagrammatic representation for the preceding code:

Figure 1.2 :An impure function

Comparing addThem and addP, which of the two is clearer to reason about? Remember that while debugging, we look for the trouble spot, and we wish to find it quickly. Once found, we can fix the problem quickly and keep things moving.

For the pure function, we can take a paper and pen, and since we know that it is side effects free, we can write the following:

addThem(3, 4) = 8 addThem(1,1) = 3 …

For small numbers, we can do the function computation in our heads. We can even replace the function call with the value:

scala> addThem(1,1) + addThem(3,4) res10: Int = 11 scala> 3 + 8 res11: Int = 11

Both the preceding expressions are equivalent. When we replace the function, we deal with referentially transparent expressions. If the function is a long running one, we could call it just once and cache the results. The cached results would be used for the second and subsequent calls.

The addP function, on the other hand, is referentially opaque.